|

|

San Pedro Springs

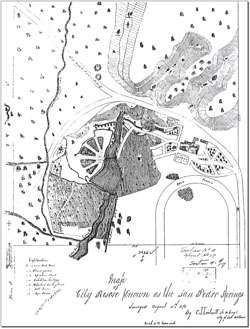

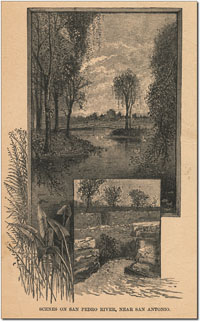

The Springs and a small natural lake just below the Springs were a favorite meeting place and campsite for native Americans for thousands of years. The bones of mastadons, giant tigers, dire wolves, Colombian elephants, and extinct horses have been found here, along with projectile points and stone tools. In early historic times, a band of Coahuiltecan Indians known as Payayas called the Springs and their village there Yanaguana. After European settlement, the site was the social and recreational center of San Antonio for many decades, and a number of important old roads, including the Camino Real (King's Highway) radiated from this point. Early travelers would sometimes confuse these Springs with another major cluster of springs four miles to the northeast, San Antonio Springs. A nearby street, Calle del Camaron was named for the abundant crawfish that were found in the Springs and Creek. Limestone quarried from just northwest of the Springs provided stone for many of the town's early buildings.

Spring e is the largest. Springs a and b, in front of the bandstand, were sealed by the City Parks and Recreation Department many years ago to divert more flow to the other Springs. There were many additional springs in the area where the swimming pool is today; their locations have been lost to history. In 2014, artist Susan Dunis created a series of paintings for these pages that depict a family of Lower Pecos natives on a sacred pilgrimage to the Edwards springs sites about 4,000 years ago. Each painting illustrates a different aspect of cultural importance of the Edwards springs. In this painting, the fifth in the series, the theme is the use of the springs for gathering food and tools, and their use for simple pleasure and relaxation. While the younger family members take a swim in the sun-drenched springs, the men are selecting chert for point-making, collecting wild grapes, and fishing.

Spanish exploration and settlement By 1680 the Spanish had begun to fear French expansion into lands claimed by Spain, and between 1709 and 1722 several Spanish entradas, or formal expeditions, made their way across Texas. These explorers realized the gentle plain below San Pedro Springs was a strategic spot for a permanent stronghold against French incursion. Father Isidro Felix de Espinosa, one of the leaders of an expedition in 1709, gave the Springs their name and provided the first known description:

Espinosa's description of an irrigation ditch with sluices and terraces has often been interpreted as evidence that native Americans were practicing irrigation here or that earlier Spanish settlers were already present. However, I. Waynne Cox pointed out there is no evidence for either interpretation in any other text or in the archaeological record (in Houk, 1999). There is no evidence anywhere else in the San Antonio River valley that inhabitants became farmers. M. B. Collins has suggested that because the plant and animal resources were so rich and diverse, efficient hunting and gathering prevailed and the labors and limitations of food production were looked upon with disdain (Collins, 1995). The terraces referred to by Espinoza may have been natural limestone outcroppings that were later quarried. In this region, limestone layers erode at different rates, resulting in hillsides having a stair-step appearance that can be mistaken as man-made. Another Franciscan missionary, Antonio de San Buenaventuara y Olivares, also arrived with Espinosa's 1709 expedition and became interested in this area of Texas and the intelligent Payaya Indians. He began a nine year campaign to build a mission here. He got his chance in 1718 when Martin de Alarcon, a Spanish soldier of fortune and governor of the province of Texas, was sent to establish a presidio and settlement. Many delays in mounting the expedition led to acrimony between Alarcon and Olivares, and they took separate routes to their destination. On May 1, 1718, Olivares broke ground just west of San Pedro Springs, built a hut of brush and grapevines, offered Mass, and named his mission San Antonio de Valero. This marked the establishment of San Antonio's first permanent settlement by Europeans. Meanwhile, Alarcon chose the creek just below the Springs for the site of the Royal Presidio, which became the focal point of Spanish defense in western Texas and San Antonio.

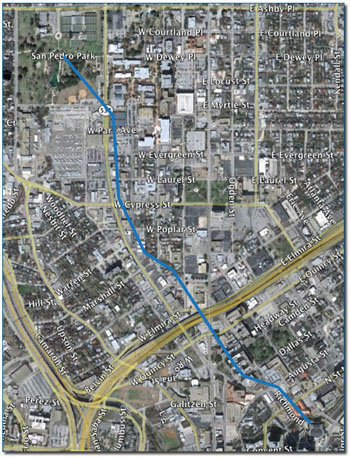

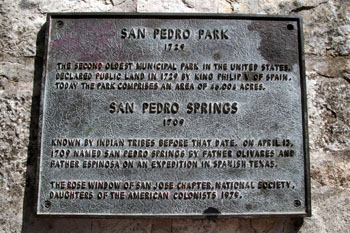

Olivares' little mission later became known as the Alamo and the shrine of Texas liberty. So originally, the mission was not on the San Antonio River where the famous battle was fought, but here at San Pedro. After establishment west of the Springs in 1718, the mission was moved in 1719 to the east side of the Springs where farmland was better, and then was moved to the location now occupied by St. Joseph's church. Hurricane floods destroyed it in 1724 and the mission was then moved to its final location on the banks of the San Antonio River (Noonan-Guerra, 1987). By January of 1719, Alarcon was directing the construction of San Antonio’s first irrigation canal, or acequia, to carry water from the Spring headwaters toward agricultural lands. Eventually, a system of seven canals diverting water from both San Pedro and San Antonio springs would form the framework around which present-day San Antonio grew up. There are many streets in San Antonio, such as Saint Mary’s, South Flores, and Presa, that were originally laid out to follow the contours of the canals. This explains their still meandering nature, although the canals are long gone. By replotting the metes and bounds of land grants that bordered the canal, I. Waynne Cox established that the first canal at San Pedro started on the eastern edge of the Springs and flowed southeast 1,308 feet to the east of San Pedro Creek, where it turned slightly more to the east to intersect a projection that is now Richmond Avenue. It then paralleled the general course of present day Richmond Avenue and discharged into the San Antonio River where the Municipal Auditorium (now the Tobin Center) is today (Cox, 2005). In 1729, not long after the city's first acequia was in operation, San Pedro Park was established when King Philip V of Spain declared the land surrounding the Springs to be an ejido, or public land. Two years later, in 1731, the ejido was used for the first time in the public interest when the commander of the Royal Presidio designated it the temporary farming land of 56 men, women, and children who had just arrived from the Canary Islands. As such, the land around the Springs was also the site of San Antonio's first official permanent settlement by European civilians. Until their arrival, the only official colonists had been the military and religious missionaries. As occurred elsewhere along San Antonio's acequias, early unofficial settlers had been using the irrigation system and had developed farmlands, but they did not have formal title to the land and were forcibly displaced by Canary Islanders and others who received royal land grants. The remains of an acequia that can still be seen in the Park today (photo below) were not from the first acequia, they are a remnant of the Alazan Ditch, built in 1874 by Anglo businessmen. The old world masters that constructed the first acequias were highly adept at designing and executing perfectly functioning canals, while the Alazan Ditch, with a design dictated by City Hall, never functioned correctly. A casual inspection of the canal’s remains today will reveal that it starts at a higher elevation than most of the spring outlets. In 1874, after work had begun, the press reported the city engineer had “discovered that water will not run uphill” (San Antonio Express, April 16, 1875). Though declared a public land in 1729, it took more than a century for the area around the Springs to take on the appearance of a modern day park. It remained little more than an outpost where armed travelers could graze their pack animals and obtain water. Around 1785, Philip Nolan, one of the first English-speaking adventurers in New Spain, brought his pack train to the site and skirted Spanish law to establish a trading network that created American-style commerce in Texas.

Military uses of the Springs In the spring of 1813, revolutionists who favored a separation of Texas from Spain formed the Republican Army of the North and achieved victory over Spanish Royalist forces in San Antonio. They declared Texas to be independent, but the first Texas Republic was shortlived, as almost all the Republicans were massacred at the Battle of Medina in August of the same year. Following the battle, the city was systematically raped and pillaged and almost became a ghost town. Records of Spanish land grants in the village archives were lost, such as the one that declared an ejido around San Pedro Springs. Texas finally achieved independence in 1836, but the following decade was one of continued carnage and battles against re-invading Mexican troops and marauding Indians. By 1841, Texas Rangers headquartered in San Antonio under Captain Jack Hays had become experienced riders and Indian fighters. When they were not on expeditions against unfriendly Indians or Mexicans, they would join local Mexican cowboys and Comanche warriors at San Pedro Springs for riding contests and exhibitions of amazing feats of horsemanship. John Duval's firsthand descriptions of these riding matches are the earliest recorded use of the site as a recreation center. He wrote:

Opposite to them were the Texas Rangers:

and also:

After the arena had been cleared of the large crowd that had come to watch the show, the contest began:

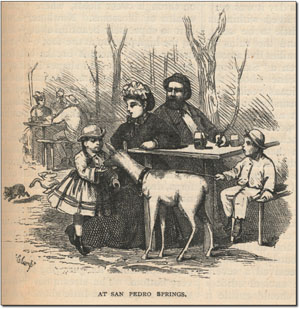

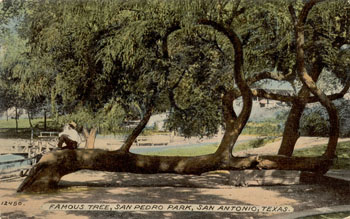

Duval described how other portions of the contest involved shooting arrows and bullets into a target while riding past at full speed, shooting imaginary foes while hiding under a galloping horse's neck, and numerous horseback acrobatics. In the final event, the contestants broke in several wild horses, and then the judges awarded first prize to a Ranger and second prize to a Comanche warrior (Duval, 1892). In 1845, anticipating war with Mexico, the United States sent troops into Texas under Colonel William Harney, and his three companies of the 2nd United States Dragoons pitched camp near the Springs, making the Park the first home of a U.S. garrison in Texas. The city recognized the advantage of having a permanent military presence and offered 100 acres of free land around the Springs for establishment of a fort, but Harney declined, telling City Council "The low land is unhealthful and the open space makes it easy for Indians to attack" (Crook, 1967). Although the army did not make a permanent base at San Pedro Springs, their encampment there began a relationship with the U.S. military that has lasted until this day and profoundly impacted San Antonio. In 1917, Mayor Sam C. Bell addressed a gathering of Army representatives and Chamber of Commerce members, and he told of the soldiers having come to town in 1845: "They pitched camp at San Pedro Springs and, finding it an ideal spot for military headquarters, have never left. The soldiers have been marrying the daughters of San Antonio for years, and that is why the Alamo City is called the mother-in-law of the Army" (San Antonio Light, August 17, 1917). In 1849, some of the troops that had fought with William Jennings Worth in Mexico camped around springs in San Antonio during a cholera epidemic in which Worth and 600 others died. The campsite came to be known as "Worth's Spring", possibly referring to a location at San Pedro Springs Park (see the FAQ on Worth's Spring). In 1851, with original records missing, the City sought to re-establish the boundaries around San Pedro Park. Officials had the boundaries marked off as remembered by older residents, and then the city initiated legal proceedings against those it considered trespassers. In the case of Lewis and Others v. San Antonio, the District Court found in favor of the City and granted title to 46.004 acres that is now San Pedro Park. In 1852 the City sold two adjacent lots to Jacob J. Duerler, who built his house within 200 feet of the Springs on city land. In 1854 the City Council officially granted him permission to live on the property. In September of that same year, a two-day county agricultural fair was one of the first large community events to be held in the Park. Farmers and stockmen brought the best samples of their products to compete for prizes. Two years later, in 1854, the United States Army experimented with the use of camels in south Texas and temporarily stabled the animals in San Pedro Springs Park. In 1860 Sam Houston delivered a two-hour speech against secession at a large political rally at the Park. During the Civil War, Confederate soldiers used the Park as a prisoner-of-war camp. These intense uses by the military damaged the Park and in 1863 the City Council prohibited military encampments and livestock. On April 5, 1867, the San Antonio Herald announced the arrival of the 9th Cavalry of Buffalo Soldiers, the storied all-African-American unit. They set up camp near the Springs, and reporters commented on how tidy and well-mannered the soldiers looked. The unit remained in San Antonio for three months, leaving in July to spread out across west and south Texas to protect mail and stage routes and engage in battles against bandits and Indian raiders. San Antonio's Amusement Park In 1864, Jacob J. Duerler petitioned the city for a 20 year lease of the property in exchange for much-needed stewardship and improvements including fencing, planting of trees and shrubs, and cleaning the Springs. Under Duerler's management, the Park became San Antonio's amusement center, with an amazing array of attractions and interesting improvements to the grounds. Duerler created five fish ponds, planted flower gardens, constructed a speaker's stand and exhibition building with a ballroom and bar, rented boats, built a horse-race track, and opened a small museum and zoo.

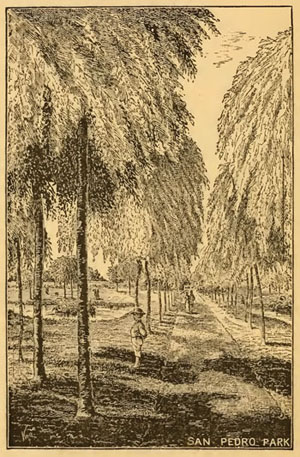

In 1873, Edward King, writing for Scribner's Monthly Magazine, captured the spirit of the Park:

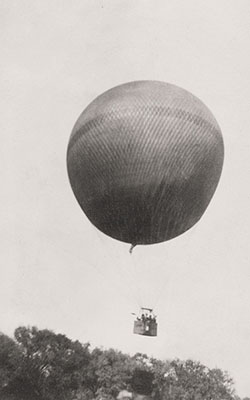

Also in 1873, a large colony of genuine gypsies descended upon and camped at San Pedro Springs. The city was greatly attracted by the visitors, and large crowds gathered about the gypsy camp whose members provided entertainment and amusement, while others begged money from the spectators. Park manager J. J. Duerler died unexpectedly in 1874 from injuries suffered in a fall, and and his son Gustave took on management of the site until 1877, when city records indicate that Duerler's son-in-law Isaac N. Lerich was representing the Duerler heirs in management of the Park. Duerler was buried in the Park but by 1886, his grave had been descrated by vandals and the monument fallen into decay, so his son had his remains disinterred and removed to the city cemetery. In 1878 a mule-drawn cart began continuous runs from the Alamo Plaza to the Park, making it more popular and accessible than ever. About this time a bandstand was added, and there were hot-air balloon rides and daring parachutists, shooting matches, and horse races. Even while the Park was become more popular, dissatisfaction over the management provided by Lerich was growing. The City Council initiated fence repairs and tree trimming on its own, and in 1880 passed a strongly worded ordinance that directed Mr. Lerich to make specific improvements. By 1883, the Duerler heirs had sold their unexpired lease to Frederick Kerbel, and City Council voted unanimously to approve the transfer. In that year, the General Directory of the City of San Antonio described the Park this way:

In 1884, the new lease holder Kerbel made many improvements. On March 8 the San Antonio Light reported:

The Grotto referred to is a strange little conical building with a pipe in the center that delivered water to the top, allowing it to run down the sides and create a habitat for moss and ferns. In her 1962 book San Pedro Springs Park, Cornelius Crook reported it was originally built as a Victorian summer home when cool summer retreats were all the rage. The fountain appears to have been added in 1884. A local legend says it was used as a cage for bears, but I haven't found any firm evidence of that, and the same article mentions "the bears are in their old place in the pit." Another legend says it housed the entrance to a tunnel to San Fernando Cathedral and/or the Alamo, but that is definitely not true. In 1885, Gustave Jermy, a Hungarian naturalist, opened the Museum of Natural History, a forerunner of today's Witte Museum. He acquired many interesting specimens of Texas, mostly by donation, including fossils, rare birds, animals, and lizards. Around 1886, a newsboy named Willie Ivy conducted an aerial stunt in which he walked a rope stretched across the water in San Pedro Park at a height of about 100 feet. Ivy went on to become a world-famous aeronaut, conducting many feats of aerial daring across the country and in Europe. He was also credited with making the first balloon ascension in San Antonio and was the first in the world to leap from a balloon using a parachute, a feat witnessed in the Park by thousands of San Antonians and visitors from surrounding towns. By 1888 David Menk had taken over the Museum enterprise and he added additional specimens such as bald eagles and elk. He also added oddities like a "genuine snow white opossum", and it was the only place in town to see Chinese waltzing mice and an anteater taught to walk a slack wire. Some other interesting features in the Park at this time were a large star-shaped rock structure that had an interesting fountainhead at its center, and a very popular, picturesque path called Lovers Lane that began at the east end of the bridge that spanned the lake. Some of the large trees that lined the path are still there. It would be difficult to guess how many romantic interludes occurred here! Another important element of San Antonio's love-making was bicycling in the Park. After paths were improved and smoothed, the Light newspaper reported the site had become a mecca for cyclists, with large numbers gathering there every night. At San Pedro, "more than one happy love was born on a bicycle built for two." There was also a race track for cyclists - an eighth-mile course made of boards with curves so steeply banked that riders had to get a running start to acquire enough centrifugal force to make it. One Sunday afternoon, the entire town turned out to see "Human Pitted Against Beast", in which two cyclists outran a horse that galloped around the outside of the track. During these years, the Park was in what we may retrospectively call its "heyday". In 1886, the temperant Christian women were pretty much correct in their assessment of San Antonians; one need only attend any of today's Fiesta events to be convinced the people here have not changed very much:

The "Gambrinus" referred to was a legendary culture hero of Europe, celebrated as an icon of beer and joviality. The article is from the San Antonio Daily Express, August 7, 1886. Today, we don't really race fat women anymore, but that's about the only difference.

The Cradle of San Antonio Sports Almost every single sport that became popular in early San Antonio started at San Pedro Springs. Many of them were played for the first time in Texas at San Pedro. In 1935, the Express newspaper offered a look back at the beginnings of sport in San Antonio:

A Short List of San Pedro Events The list of activities and events at San Pedro Springs during the heyday years is simply endless. From newspaper accounts, I assembled a very abbreviated list to illustrate the scope and importance of this place to San Antonio's 19th century social scene:

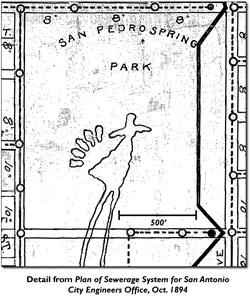

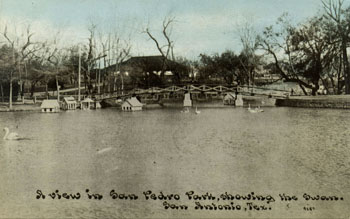

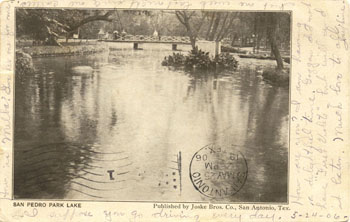

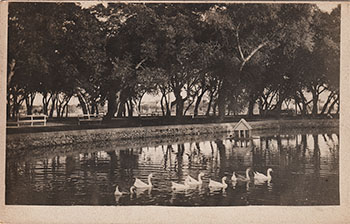

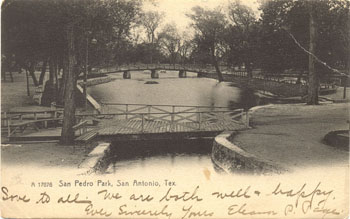

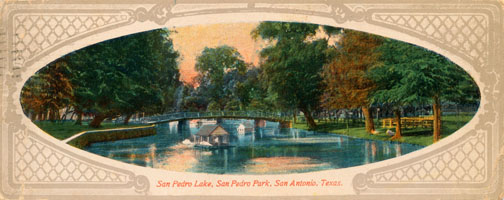

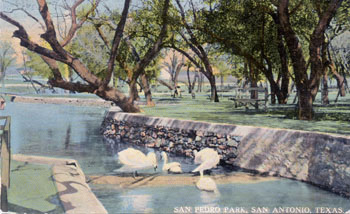

The Beginning of the End By 1891, wells were being drilled into the Edwards Aquifer. On August 1 of that year, the impact of one well was documented in the San Antonio Daily Express. The event created great excitement, but it was not recognized as the harbinger of the Spring's end: Although the completion of this particular well actually increased the flow, the drilling of many others was about to ensure a long, slow decline of the Springs towards intermittent and meager flow, and then long-term cessation. Also in 1891, upon expiration of Kerbel's lease, the City Council voted to assume management of the Park. Over the next few years, both springflows and the Park itself suffered serious deterioration. In 1897 Mayor Bryan Callaghan was elected for a second term and took a great interest in renovating the Park. The lake was cleaned and its stone walls repaired, Duerler's ponds were filled in and his pavilions demolished, and a new bandstand was constructed. Grass, tropical plants, caladium, and water lilies were added, and driveways, bridges, benches, pathways, planting beds, and a boat landing were built. Several of the smaller springs were artistically walled in with rock and pretty little canals were built to carry water to the lake.

The Park formally reopened on August 11, 1899, but by this time it was surrounded by San Antonio's rapidly growing residential neighborhoods, and the drilling of numerous wells ensured that springflows would never again be as vigorous and reliable as in the past.

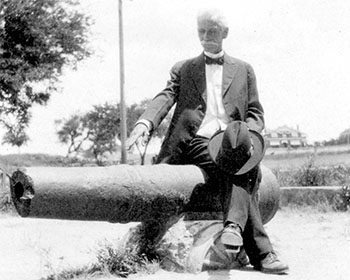

The Alamo Cannon (cannons?) In August of 1899, seven cannons were recovered during excavation for the foundation of the Maverick building at the corner of Houston Street and Avenue D (now Broadway), which would have been within the Alamo compound during the famous 1836 battle. The largest of these cannons, covered with a rust and with a broken muzzle, "was placed in San Pedro Springs Park near the bandstand as an ornament of historical interest." It was about six feet long, having once fired a ball of about 3 1/2 inches. At the time it was suggested that all seven cannons were probably spiked and buried by Texian rebels, who had more guns than ammunition, to keep them from falling into the hands of the Mexicans in case they lost (The Daily Light, August 8, 1899). Only four months later, on Christmas Day, an idiot rammed a big charge of powder down the cannon's throat, drilled the rust out of the old fuse hole, placed a fuse in it, and set it off. The Daily Light reported "the boom was followed by the sounds of pieces of iron falling in all directions and when the excited residents of that part of the city arrived at the point where the gun had lain, they found only part of the muzzle - the back end had been blown to pieces." The next morning Mr. David Menk, custodian of the Museum and Zoological garden, "visited the gun and to his astonishment found a fresh charge of powder in the back of that part of the gun which was left and upon closer investigation, a few feet away he found an iron cannon ball, covered with rust, which fit exactly in the rear end of the unexploded part of the gun, where fresh powder could be seen." The Light reported that Mr. Menk "...at once solved the problem. The old gun while in use in the Mexican war was loaded when spiked and buried. It had lain under ground all that time charged for mischief. When the mischief maker of Saturday night charged the ancient gun his load of powder only went down the barrel as far as the rusted ball and it was this charge which Mr. Menck found after the explosion. When the fuse-hole was drilled out and the fuse inserted, instead of setting fire to the fresh charge of powder it had set fire to the charge of powder placed there 63 years ago. The ball could not be forced out of the rusted muzzle, consequently the rear part of the gun exploded." (The Daily Light, December 28, 1899) Mr. Menk displayed the ball and some pieces of the exploded cannon in his museum. What happened to the cannon after that is an enduring mystery that Alamo enthusiasts are still trying to figure out. There are a handful of pictures and postcards that show a cannon in the Park, but none can be affirmatively dated to a time before the 1899 explosion incident. It is unclear if a second cannon was moved to the Park or if the first cannon was somehow reconstructed and displayed. In 1917, confederate veteran Charles T. Smith told a local newspaper tales of what it was like in old San Antonio, and he claims that he and several boys, imagining the cannon full of gold, set about to break into it:

Researchers are skeptical of Mr. Smith's story. Sawing an indentation with yarn seems like a yarn in itself. And there are no other accounts of a cannon in front of the "Indian fort" (the Block House); all other accounts place the cannon near the bandstand. Also, the original newspaper account from 1899 when a cannon was dug up and moved to the Park reported the muzzle as already broken. The cannon has long been thought to be not just any Alamo cannon, but THE 18-pounder cannon that Alamo commander William B. Travis fired at Santa Anna's troops in defiance after they demanded his surrender before the famous battle. In 2020, researchers with the Alamo Trust, Inc. Collections Team used the photo below to determine the cannon was likely not a true 18-pound cannon, but a smaller one that had been modified to fire a larger ball (the words "18-pounder" refer to the weight of the cannonball the weapon fired). The group create a replica of the cannon that is now displayed at the Alamo.

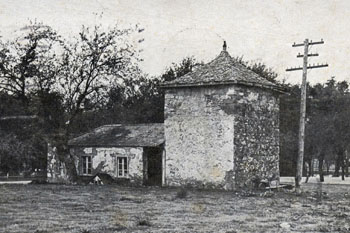

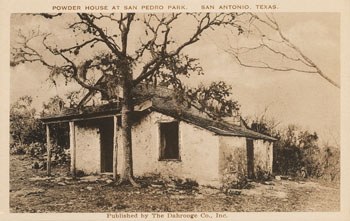

The Block House and the "When Was It Built?" Mystery Several hundred feet east of the Springs is an old small stone building with vertical slits for rifles that San Antonio legend says was used as an early refuge against hostile Indian attacks. Another old San Antonio legend says the structure was built by the Texas army to store powder. Others say it was only a hay barn and that in later years, J. J. Duerler used the little building as a smokehouse. It's date of construction has not been firmly established. A legend that it is the oldest building in Texas can be traced to an article that appeared in the Austin American-Statesman on January 31, 1932, written by Samuel E. Gideon, an architect on the UT faculty who served on a committee for the preservation of early architectural specimens. He wrote:

If this is true, it would predate Olivares' 1718 mission. Serious doubt is cast on this theory by the fact that that no mention of the building is made by the early friars who carefully recorded descriptions of the land. It also seems very unlikely that Spanish soldiers before 1716 would have had the resources or wherewithal to construct such a stout stone building. There is a bit of second-hand evidence that either the Block House or another building that was known as the Powder House might be dated to a time when the original Canary Islanders farmed the area, sometime after 1731. When the San Antonio Daily Light reported on the death of Thomas A. Rodriguez on April 9, 1903, it mentioned his grandfather was the head of one of the Canary Islander families and owned all the land between the San Antonio River and San Pedro Creek. The paper mentioned the elder Rodriguez had a flax farm at San Pedro Springs and "built a portion of the old stone house still standing in the park." It is not clear if the reference is to the Block House or the Powder House, but the implication is that something built very early was still standing in 1903. Several researchers and archaeologists have noted the building matches the style and construction techniques used in approximately the mid 1800s, and excavations have revealed no artifacts earlier than that. In 2015, archaeologists working for the University of Texas noted the Block House does not appear on a very detailed, instrument based survey map prepared in June of 1899 by engineer E. G. Trueheart just prior to extensive improvements in the Park (Mauldin, et. al., 2015). On this map, the archaeologists plotted the location of the missing Block House and it came out covering a portion of the old Upper Pavilion. They concluded that:

However, there are many lines of evidence that indicate this suggestion is wrong, and at least one solid proof the building was already there in 1899. First, postcards dated to 1909 show a Block House that already appears very old, with peeling plaster and filled-in rifle slits. It's true it could have been built to look old, but by this time the building was already central to local legend and lore. It seems unlikely the entire public would have developed amnesia and not remembered a recent construction. For example, the little fort was central to Richard Wallace Buckley's 1911 story The Lure of Lolita (see below or read the complete transcription here). It's possible that Mr. Buckley constructed an old story around a building that would have been rather new in 1911 if it had been built after 1899, but it would be weird and a bad choice, because everybody would have been on to him. There is also a circa 1910 postcard showing a very old-looking Powder House, which likewise does not appear on the Trueheart Map, neither did he record outhouses that are known to have been there, so it seems clear Mr. Trueheart simply did not record everything on his 1899 map. There are also newspaper articles from the 1930s that report on the efforts of Mrs. Ida Schweppe to restore the structure and research its history. Once again, this would have seemed to involve a general amnesia. If it had been built after 1899, there would have been plenty of people around who remembered its construction and Mrs. Schweppe's research would have been rather simple. But concrete evidence against the archaeologist's conclusions is found in an article from the Daily Light on July 14, 1899. The paper reported on the improvements being made and says:

From this, it seems clear the Block House did indeed exist when the Trueheart Map was prepared and is older than 1899. The fact that archaeologists plotted the location of the Block House on the Trueheart map and it came out covering a portion of the Upper Pavilion suggests that perhaps this map was not as accurate or detailed as believed. So when was it built? We don't know, but the most likely date seems to be the mid 1800s.

Legends of San Pedro Springs There are many haunting legends and mysterious tales associated with the San Pedro Springs and Park. For example, Francisco Rodriguez, a Canary Island immigrant to Texas in the 1730's, is reported to have buried several chests of gold and silver coins near the Springs, perhaps in caves under the northern edge of the Park. He died before telling anyone the location, and they have never been found. (Brune, 1975). The same caves were reputed to have been used as hideouts for bandits in the mid 19th century. Another legend that persists to this day concerns a tunnel that once connected the Alamo and San Pedro Springs Park. The passageway was supposed to have been formed by a cave that ran much of the distance between the two sites, beginning in the Flag Room at the Alamo. Some say the opening at the San Pedro Park end was in the "bear pit", a small quarry that was a part of San Antonio's first zoo and that has been covered since 1897. Others say the tunnel emerged under the gazebo and was so large one could ride a horse through it. Geologists say it's highly unlikely such a tunnel ever existed because it would have had to go underneath the San Antonio River. Today, there is a tunnel under the Alamo, but it wasn't built until the 1980s, for the purpose of flood control (see the San Antonio River page). The Lure of Lolita One of the legends of San Pedro Springs, The Lure of Lolita, appeared in a 1911 newspaper short story and involves the inhabitants of the old Block House. The article says that about 60 years earlier, around 1851, a man named Vincent Boone sought shelter from a storm at the Block House. A very old, dark man who called himself Pedro Lara answered the door and, noticing that Boone carried a fat money bag, offered him food and the opportunity to stay the night in a hut nearby. He introduced Boone to Lolita, an extremely beautiful young girl that Lara said was his daughter. Boone was wary of Lara, and decided to spend the night with his gun on his chest and his clothes on. During the night, Boone heard noises in his hut, struck a match, and saw Lara approaching with a knife. The match went out, and Boone shot into the darkness. He lit another match, but Lara was nowhere to be seen. Then, Lolita ran up to the hut and revealed a trap door that led to a shallow cave where Lara lay dead. She begged Boone for mercy, saying she was not Lara's daughter but had been bought by him as a young child and had been used time and time again to lure travelers into staying in the hut so Lara could rob and kill them. She said the cave already contained the bodies of two people Lara had killed. Whether or not any of this is true no one can say. But in 1900 city workers were extending San Pedro Avenue past Dwyer Street and found a shallow cave with three skeletons.

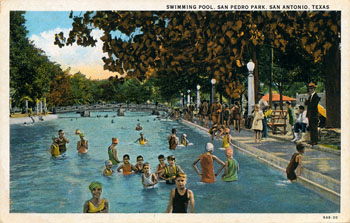

20th Century Decline and Renewal As the 20th century began, an exploding number of Edwards wells intercepted greater and greater volumes of water that would have been destined to become springflow at San Pedro. In 1912, the city refused to allow the very popular zoo to occupy city property any longer without admitting people for free, so heirs of Mr. Menk's successor, Jacob Amreihn, sold the zoo to I. S. Horne of Kansas City and all the animals were crated and moved. Still, the Park remained popular, and another major renovation began in 1915 and extended into the 1920s. Tennis courts, a library, and a community theater were constructed. In 1923, San Antonio's first municipal swimming pool was built in the old lake bed, it was a sort of naturalistic lake replenished by the Springs. A formal opening was held on April 17, 1923 as part of the city's annual San Jacinto festival, and newspaper advertisements promised "a remarkable program of aquatic events." The city built the pool and two Chamber of Commerce organizations cooperated in erecting a bath house. The idea for a swimming pool came from children in 1913 who expanded on Mayor Clinton Brown's suggestion that some swimming holes could be created in the San Antonio River using artesian well flow. Instead, they suggested a pool at San Pedro. On July 10, the Light newspaper published one of these letters from young Raymond Turner of 742 Leal Street:

The nickle mentioned in young Turner's letter referred to Mayor Brown's suggestion that if the city could not see its way clear to provide the money for the upkeep of a wading and bathing pool, it could be made self-sustaining by making a minimum charge.

Before the first swimming pool was constructed, there was very little recreation based on actually getting wet. Not a single one of the more than 50 early postcards I have collected, nor any early stereoview cards, show anybody actually in the water. Apparently, there were a lot of alligators. In 1887, the Daily Light newspaper reported on an accident:

By 1922 when the swimming pool was constructed, the alligators had been moved to what appears to be the main Spring outlets, and a full-blown kerfuffle erupted when the Evening News reported that dogs from the city pound were being fed to them alive:

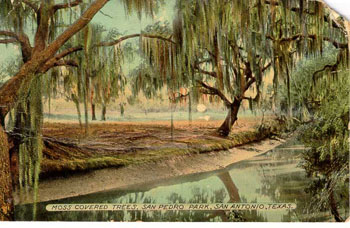

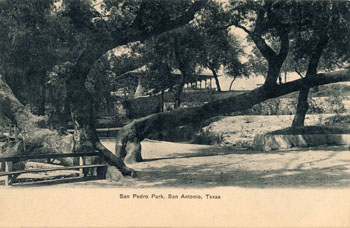

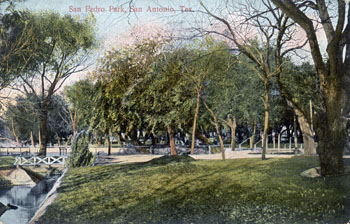

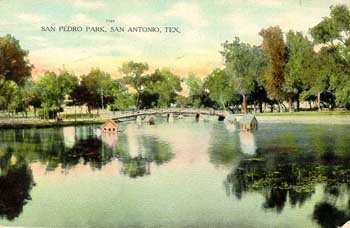

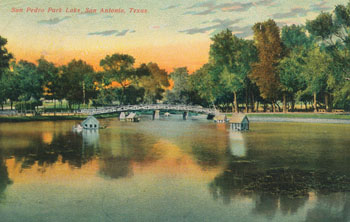

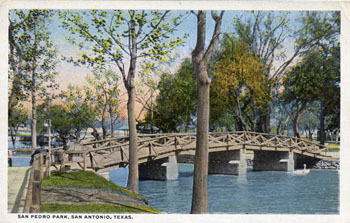

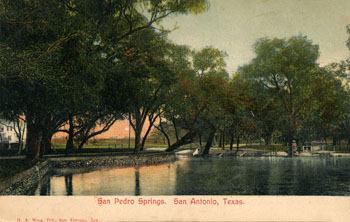

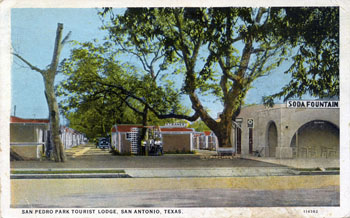

By the early 1920s, springflows became meager and intermittent, but until then the Park remained a central San Antonio attraction. An astonishing variety of early 20th century postcards depicting San Pedro Springs can be found in area antique stores and on eBay (see collection below). Mostly produced between 1900 and 1920, they attest to the popularity and importance of the Park during these years. Their complete disappearance after about 1925 confirms that springflows and the Park itself were in serious decline by then. Crawfish and other aquatic life that was previously reported to be in abundance began having a difficult time surviving. Uses of the Park began to focus less on the Springs and pool and more on other activities like theatre-going and seasonal ice skating. On October 15 of 1930, the first airmail flight out of San Antonio to the West was celebrated when Miss Jacke Hendricks broke a ribboned bottle of water from San Pedro Springs over the propellor of a Stearman biplane at Winburn Field. From here, planes intercepted the east-west transcontinental airmail route at Big Spring.

By the 1940s, springflows were reduced to almost zero by drought and pumping, and there was no longer sufficient water to fill the natural swimming pool, so it stood empty for a decade. In 1954, with assistance from philanthropist and grocer Howard E. Butt, it was replaced by a smaller, rectangular pool that was filled with chlorinated municipal well water. In the same year, the bandit caves where Rodriguez may have buried the gold were destroyed by construction of the McFarlin Tennis Center (Rybczyk, 1992). The Springs remained mostly dry for the next 35 years, and several new generations of San Antonians grew up swimming in a municipal pool much like any other, without much remembrance or personal connection to the Springs. But after record rain events in 1991 and 1992, the main Springs flowed profusely again and dozens of long-forgotten tiny springs bubbled up all over the Park. For several months, the Spring pools were once again a magnet for swimmers and waders, although such recreation was officially disallowed. In 1993 the City adopted a Park Master Plan that called for showcasing the Springs and restoring the original lake as a swimming pool, and voters passed a bond issue in 1994 to fund renovations. In 1996 disputes erupted between citizens groups and city staff over what to do with the McFarlin Tennis Center and several baseball stadiums that impeded open-space views to the Park's interior. Many considered the Tennis Center an aesthetic eyesore - it's stadium riser seating and light towers loomed over and dominated the Springs. Another controversy involved placement of a fence around the restored lake. Almost everyone agreed a fence around a natural-looking lake would look stupid. In 1996 city legal staff decided no fence was needed and noted "...the city will incur the same type of liability that exists with Woodlawn Lake and lakes and ponds in other city parks." But at the last minute in 1998 the city attorney's office changed its mind, describing great liability exposure for the city if no fence was built. A design for a permanent stone pier and metal fence was presented, and neighborhood objections were loud and immediate. A compromise was reached - the fence was redesigned for easy removal and storage most of the year and would only be left in place when city swimming programs take place during the summer. In July of 1998 work was finally set to begin on the makeover of the historic Park and Springs. Showcasing the Springs and restoring the pool were priorities, along with a new network of wide walkways, new lighting, removal of parking to the fringes of the Park, removal of old drainage channels to create more open green space, and reconfiguration of the McFarlin Tennis Center to reduce its visual impact. Park Reopening On Saturday May 20, 2000, the beautifully restored San Pedro Springs Park reopened for public use. To give the new pool the feeling of a natural lake, it was finished in dark plaster and surrounded by a broad limestone walkway. At the opening festivities descendants of the native inhabitants, the Yanaguana Drummers, shared a tribal ceremony and a mesmerizing, riveting drum performance. Then there were many long speeches about everything the waters and Park have meant to people over the years. It seemed ironic that at the last minute no one was allowed in the water. It had been announced that when the ribbon was cut, swimmers would jump in. But just before this was to occur it was announced this would "send the wrong signal" because no lifeguard was on duty and the other city parks did not officially open for swimming until May 27, a week later.

As part of the 1998 restoration, designer and fabricator Jack Robbins created this series of panels, each referencing a historical segment of the history of San Pedro Springs Park. They are attached to the lightpost bases around the Park.

The Springs and Park today Since the mid-1990s, limitations on Edwards Aquifer pumping have been in place and world-class conservation efforts have been undertaken by the San Antonio Water System and local residents. These measures have resulted in longer periods of springflow than have been witnessed in many decades. While the renovated Park still has plenty of fans, as seen below, it has never regained its former prominence as San Antonio's most beloved playground. Many long-time residents have never even visited the park - most are completely unaware it even exists and know nothing of its history and importance to San Antonio. A group of volunteers is working to change that. The Friends of San Pedro Springs Park is a non-profit support group under the umbrella of the San Antonio Parks Foundation, and their mission is to help with the restoration and preservation of the Park, and to communicate its long history. Membership is open to the public, and you can get more information from their website. In December of 2019, city leaders announced plans for $1.8 million in park improvements. Work will include a one-mile walking path, replacement of two softball fields with open green space, a public restroom makeover, repairs to the 1874 acequia, monument signage, lighting and parking upgrades, and planting of more than 200 trees.

San Pedro Springs photo gallery

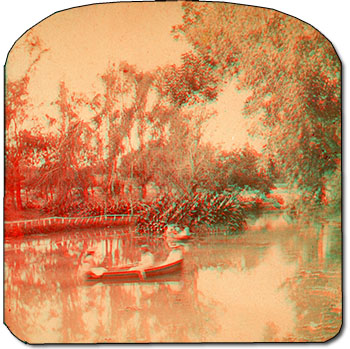

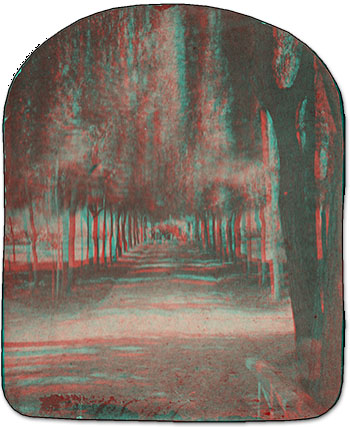

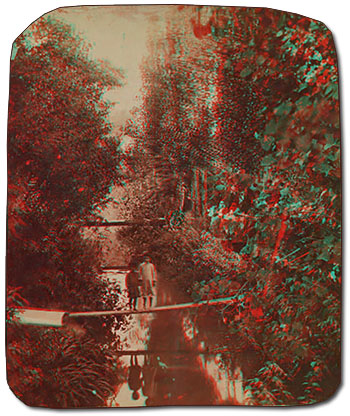

San Pedro Springs in 3D Get out your 3D glasses and view these San Pedro Springs anaglyphs, created from late 19th century stereoview cards. Click to enlarge - it's just as if you were really there. These things are very hard to acquire because avid collectors of stereoview cards on eBay apparently don't care about money.

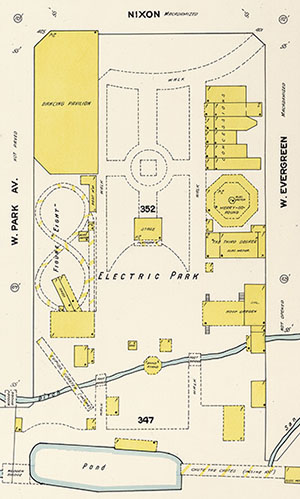

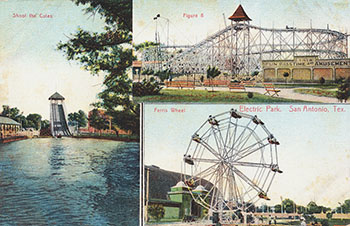

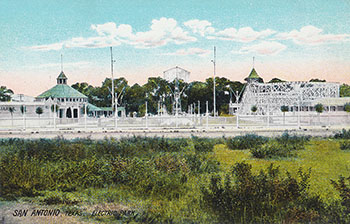

Electric Park

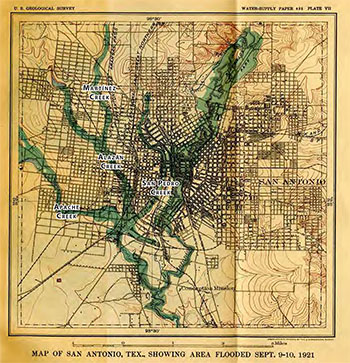

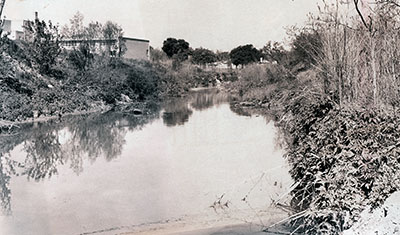

The Westside Creeks Restoration Project Below the Springs, San Pedro Creek was a vibrant part of early San Antonio, with many residents relying on it for both food and recreation. The Creek wound its way from the Springs for about six miles to its confluence with the San Antonio River. As late as the 2010s, many old-timer residents could still relay stories of fishing and swimming and spoke of a diverse and fruitful ecosystem. A series of devastating floods in the first half of the 20th century resulted ia a federal project, the 1954 San Antonio Channel Improvement Project, which brought vast changes to San Pedro Creek. In those days, “improvement” referred to straightening and concrete-lined channelization. While this provided flood-control benefits, the channels are, well, butt-ugly, and they offer zero habitat for any sort of wildlife.

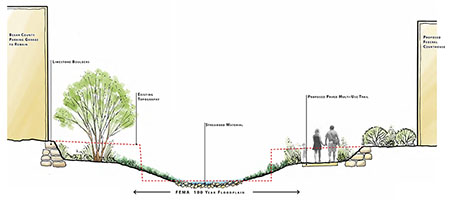

Nowadays, environmental engineers know you really don’t have to destroy a creek to get flood control benefits – it can be done in an environmentally sensitive way that gives the community an aesthetic amenity instead of a ditch. There is a strong community desire to fix the 20th century modifications and restore San Pedro Creek to something that resembles a natural ecosystem. Toward this end, in 2009 the San Antonio River Authority launched the Westside Creeks Restoration Project to accomplish restoration of San Pedro Creek and also Alazan, Apache, and Martinez Creeks. The goal is to apply design improvements in the flood control channels, create stable banks during flooding events, ensure erosion control, protect water quality during normal flow, and create habitat for fish, water fowl, and other birds and wildlife. Working with consultants and the public, a Westside Creeks Restoration Project Conceptual Plan was offered in June of 2011. The overall cost was estimated at about $175 million (get the complete Conceptual Plan here).

In May of 2013, Bexar County Commissioners Court said it had $125 million available to start the project. After engineering designs are complete, it is hoped that construction could start in 2016. By 2018, the Creek would have walkways, landscaping, small pocket spaces for gathering spaces, and perhaps even a performance venue at Confluence Park, where San Pedro Creek meets the San Antonio River. In December of 2013, Commissioners Court approved a contract for design, and there were widespread hopes the work would provide a catalyst for urban revitalization of the entire west side of downtown. In April of 2015, Commissioners Court unanimously approved preliminary designs, and the current goal is to have major portions of the project complete in time for San Antonio's 300th birthday celebration in May of 2018. Since San Antonio was founded on the banks of San Pedro Creek, the project could be a central focus of the party. By June of 2015, some elements of the preliminary designs were being criticized as too gaudy even for San Antonio. In a letter to SARA General Manager Suzanne Scott, local developer James Lifshutz said the designs were "lacking." In an email to the Rivard Report, Lifshutzt expanded on his comments to Scott. "The design of the northernmost reach expresses an inappropriate grandiosity that does nothing to honor the history of San Pedro Creek, nor the generations of San Antonians who have lived and worked on or near its banks. This grandiosity distracts from, and cheapens, the history, context, and natural beauty of the Creek – and will not age well. The showiness of the design will make it more difficult to develop land next to the creek. Rather than an amenity that enhances neighboring development, the flamboyance of the creek will be something that has to be overcome." In August, local boy Robert Hammond, who was a catalyst for development of New York City's celebrated High Line Park, paid a visit to his hometown and offered additional criticism: "The model for San Pedro Creek should be the Mission Reach, which means restoration of the natural environment, not heavy architectural intervention. The bones are there, but it needs a much lighter touch. It really needs more landscape and less architecture." Others called the designs "overdone," and "theme park-like". Officials responded that some of the design elements were simply placeholders and that community input into changes was welcome. By September, three landscape architecture firms from outside San Antonio were hired to review the plans, and new renderings of several elements looked very different than before:

In October of 2015, the city of San Antonio deeded 19 city-owned parcels valued at $4.1 million to the San Antonio River Authority, which gives SARA some of the necessary rights-of-way to widen the Creek, install walkways, and make connections to surrounding streets. It was also learned the cost of the project had risen from $175 to $206.8 million, and the City was considering funding a portion of the project with its 2017 Bond Program. Readers of these pages know that I hardly ever express my own viewpoints, but I will offer one here: In my opinion, the most important shortcoming of the whole project is that it does not connect to San Pedro Springs Park. As wonderful as the final project might be, the failure to start it at the Springs is a shortcoming that will cause future generations to wonder why our vision stopped short of the Creek's source. In December of 2015 the Commissioner's Court gave initial approval to major design changes, including a redesigned and more subdued ampitheatre with elements reminiscent of the Arneson River Theatre. The amount of private creekside properties that would have to be bought was also scaled back. In April of 2016 the Commissioner's Court authorized SARA to spend up to $4.2 million for 15 scattered parcels of land for the project. Four other properties were to be acquired by donation, and the city was to provide about $8 million in needed right of way. In May ground was broken for Confluence Park, and in June the Historic and Design Review Commission gave final approval for plans that will highlight the science and culture of San Antonio's deep relationship with water and landscape. The project will include a 30-foot tall pavilion as its focal point, a multi-purpose room with solar panels, a vegetative green roof, and areas demonstrating various Texas ecotypes. Also in June 2016 the Commissioner's Court approved a fast-track schedule for creating public art. The court previously set aside $900,000 for art installations along the Creek, to be split three ways: $750,000 for a permanent commissioned public art installation, $100,000 for a rotating platform for two movable installations, and $50,000 for temporary art projects through 2021. In September of 2016 a public groundbreaking ceremony was held that featured a performance of "Las Fundaciones de Bejar," an original mythic opera that tells the story of the ancient legacy of San Pedro Creek. Phase I was set to transform the Creek from the flood tunnel inlet near Fox Tech High School to Dolorosa Street. Bexar county added $7.8 million to its commitment by reassigning $2.8 million in transportation funds and $5 million in federal reimbursements. In December of 2017, Bexar County Commissioners authorized $19.8 million for demolition and utility work for the segment between Houston and Nueva streets. They also approved several design changes, including scrapping plans for an ampitheatre behind the Alameda Theater and a footbridge at the Spanish Governor's Palace. It was thought that a performance plaza as opposed to an ampitheatre would provide more flexibility and versatility, and the two changes will save $7 million in overall project costs. In January of 2017 work finally began on Phase 1.1. On January 8, I took the "Before" photos below from each of the major bridges from Santa Rosa Street to Dolorosa Street. The section from Santa Rosa to Houston Street was opened to the public on May 5, 2018 and I returned to capture the "After" photos, so we can compare the butt-ugly previous condition to the fabulous end product. Just before the opening, the project was rebranded as the San Pedro Creek Culture Park.

Phase 1.1 Before and After Photos

Phase 1.2 and 1.3 opened in October 2022

By February of 2018, work had begun on Phase 1.2 of the project, intended to add 1,200' to the Culture Park between Houston Street and Chavez Boulevard. This is a busy, densely developed area with lots of old infrastructure and potential to encounter historic and archaeological resources, so work here was especially challenging. Thousands of artifacts were uncovered, some dating to the Spanish Colonial period, and an old foundation of a 1700s presidio was found along Dolorosa Street. In February of 2019, Bexar County Commissioners expressed reservations about the cost of a public artwork called "Creek Lines", a piece with 30 stainless steel poles symbolizing water currents. The work had already been scaled down from a $735,000 sculpture to one that would cost $300,000. Commissioner Tommy Calvert said "This could have a distinction of being the most cost-overrun project of any governmental entity in the history of Bexar county." By June of 2019, Commissioners approved a final design for the piece, with a price tag of $425,000. It is scheduled to be unveiled in the fall of 2020. Also in June of 2019, Bexar County Commissioners approved $72.3 million for two more Phases of the project, Phase 1.3 and 2.0. These two phases will run from Nueva Street to Chavez Boulevard and from Guadalupe Street to Alamo Street (friends, I admire Cesar Chavez, but it will always be Durango Street to me). In November of 2019, Commissioners approved funding for a 250-foot wide, 15-foot tall "water wall", where people can speak or sing into a microphone, setting off a response to the sound in the form of bands of color. When there's no audio input at the microphone, the installation will highlight live programming from Texas Public Radio, which recently moved into its new home adjacent to the historic Alameda Theatre. In February of 2020, SARA received $26 million in federal reimbursements for money spent on the San Antonio River Mission Reach project, and the funds were expected to help fulfill the funding commitment for Phase 1.2. Also in February of 2020, archaeologists discovered a stone-and-mortar building foundation for the 19th century St. James African Methodist Episcopal Church near the corner of West Houston and Camaron streets. This was one of Bexar county's first black churches, founded shortly after the Civil War. It was expected the new find would impact construction, and SARA Project Manager Kerry Averyt said "That's OK. It's the Culture Park, and we want to represent that culture." By April of 2020, rising economic challenges related to the COVID-19 virus outbreak brought funding for additional phases into question. Bexar County Commissioner's Court had been contemplating a 10-year finance plan for hike-and-bike trail connections, ecosystem restorations, and other improvements along the San Antonio and Medina rivers and local creeks. But the COVID virus shifted attention to long-range funding priorities for direct human-based needs such as literacy, job training, and affordable housing. The county had also been considering a bond election for streets and highways, and Commissioners seemed doubtful they could accomplish both river/creek and transportation initiatives. In July of 2021, a new design for the area around the historic black church was unveiled that would preserve much of the space. The new design allows the public to walk on the historic footprint of the church and see the cornerstone bearing the rough inscription "AME Church 1875". In the earlier design, the area would have been part of an entertainment plaza, but the public showed an overwhelming interest in memorializing the St. James Church instead. Also in July of 2021, a city panel approved plans by Weston Urban to turn a block along the Creek into a mix of apartments, offices, and commercial space. Under the $80 million plan, the Arana and Continental Hotel buildings would be rehabilitated and a 15-story building constructed between. The firm would also restore the Melchio de la Garza house, which served as headquarters of the Texian Army during the Texas Revolution and is one of the oldest downtown residential buildings. By December of 2021, funding concerns related to COVID challenges had seemed to dissipate, and Bexar County Commissioners approved designs and $26.5 million for the final two phases of the project. A design challenge yet to be resolved was a solution for a stretch that runs through hotel properties south of Chavez Boulevard. Commissioners also approved preliminary renderings for five murals along the Creek near the Spanish Governor's Palace. In July of 2022, County Commissioners approved a study for a proposed park and walking trail that would connect San Pedro Creek with the San Antonio River Walk. There was some controversy because the city owns a street included in the proposal and it had not yet signaled its support, but Commissioners went ahead with approval. The park is known as The Link, and the study was expected to take about a year to complete. In October of 2022, a grand opening of Phase 1.2 and 1.3 was held, and the public got its first look at improvements from Houston Street to Chavez Boulevard. One of the highlights, between Houston and Commerce streets, is a 200-foot long wall of water that invites public interaction. A 1950s-style microphone is placed near Commerce Street, and when visitors speak into the microphone it sets off a cascade of colored LED lights illuminating the water. Next to the water wall, the foundation and remains of the black church discovered in 2020 was preserved and visitors can walk on a reinforced composite deck flooring where early early St. James parishioners worshipped.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||