|

|

Barton Springs

There are four main spring orifices that are the only known habitat for the Austin Blind Salamander, a federally listed endangered species. Another endangered species, the Barton Springs Salamander, was also believed to only live in these four springs until 2018, when it was discovered in a tributary of Onion Creek near Dripping Springs. These four springs are the primary discharge point for the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer. Main Spring, also known as Parthenia Spring, feeds the 900' long swimming pool. There is a dam at each end of the pool; the upper dam directs flow from Upper Spring and Barton Creek into a bypass culvert so that stormwater flows do not enter the swimming area. Old Mill Spring, sometimes called Walsh or Zenobia Spring, is just south of Barton Creek about 450' below the lower dam and is surrounded by a round limestone enclosure built by the Works Progress Administration. Upper Spring occurs about 1,200' above the swimming pool. The fourth spring, Eliza Spring, is adjacent to the swimming pool and also surrounded by a WPA structure, a deep concrete ampitheatre that used to be a swimming hole but is now reserved for the salamanders.

It has long been accepted that a groundwater divide separates this portion of the Edwards Aquifer from the central (San Antonio) portion and the large springs in San Marcos, New Braunfels, and San Antonio. But in April 2010 a study commissioned by the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority found that groundwater level data indicates the groundwater divide dissipates and no longer hydrologically separates the two segments during major droughts and current levels of pumping. As a result, there is potential for some groundwater to bypass San Marcos Springs and flow toward Barton Springs during major droughts. The groundwater divide appears to be influenced by recharge along Onion Creek and the Blanco River and is vulnerable to extended periods of little or no recharge and extensive pumping. See the complete study.

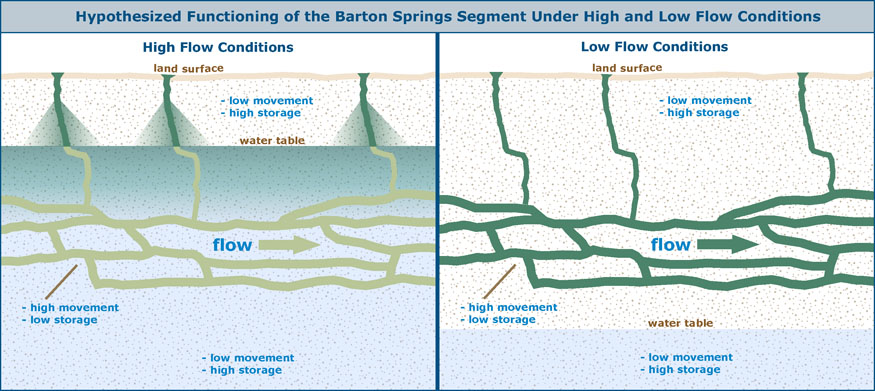

For Barton Springs, about 85% of Aquifer recharge comes from six major surface streams that cross the recharge zone: Barton Creek, Onion Creek, Slaughter Creek, Bear Creek, Little Bear Creek, and Williamson Creek (Slade, Dorsey, and Stewart, 1986). During storm events, sinkholes and fractures in the stream bed can quickly provide large volumes of water to recharge. Dye-tracing studies have found that several preferential ground-water flow paths lead to the Springs and that the four springs do not all receive water from the same flow paths (BSEACD, 2003 and Hunt, Smith, Beery, Johns, and Hauwert, 2006). Dye-tracing studies have also revealed that underground flow velocities toward the Springs are highly variable and can be quite rapid, up to six miles per day (Hauwert, Samson, Johns, and Aley, 2004). Swimmers notice that waters in the pool can become quite cloudy and turbid after rain events, especially when low flow conditions prevailed before the rain. The theory about why this occurs is shown below:

In January 2003 the pool was closed for 90 days for environmental testing after the Austin American-Statesman reported that high levels of arsenic and seven benzene-based compounds were found in the pool and upstream on a hillside overlooking Barton Creek. It was suggested that a possible source of the contamination was wastes dumped from nearby coal gasification plants that produced fuel for city lighting from the 1870s to 1928. Subsequently, it was determined the contaminant levels do not pose a threat and are from urbanization, not a waste dump. Retired hydrologist Raymond M. Slade, Jr., who supervised and authored many scientific studies on Barton Springs during his working career, prepared a detailed professional opinion on the matter and you can read it here. Mr. Slade concluded that although the water quality of Barton Springs is still well within swimming criteria, it is likely that uncontrolled urbanization in the watersheds feeding the Springs will eventually cause Barton Springs to be degraded to the extent that it must be permanently closed to swimming. In 2006, the United States Geological Survey published a Scientific Investigations Report that summarized water quality sampling performed from 2003 to 2005. Barton Springs was found to be affected by persistent low concentrations of atrazine (an herbicide), chloroform (a by-product of drinking water disinfection), and tetrachloroethane (a solvent). Concentrations peaked 1-2 days after storm events, and Upper Spring was found to be more contaminated and influenced by a contributing flow path that is separate from those leading to the other springs under all but stormflow conditions. The geochemical response at the Springs after storm events led the authors to conclude that when there is flow in the recharge streams, water directly enters conduits and is transported straight to the Springs. When there is no flow in recharge streams, water drains from the surrounding limestone matrix into the conduits that feed the Springs. You can get the report from the USGS website or right here. Citizens have been fighting for decades against insensitive development that threatens Barton Springs. In the 1990s, residents overwhelmingly passed a Save Our Springs ordinance that would have implemented strict development controls. It was subsequently nullified by the state legislature, which passed a law allowing any development plat already on file to be completed without regard to the new controls. In 2008, the fight to preserve Barton Springs was the subject of The Unforseen, a documentary co-produced by Robert Redford, who learned to swim there as a child. The movie uses the struggle over development in the Barton Creek watershed to illustrate the many clashes between private property rights and resource protection that are occurring across the country. The film drew great reviews, but some developers said it went too far and portays them unfairly. Environmentalists said the movie is not hard enough on those who would develop lands at the expense of common resources like Barton Springs.

In May of 2011 the United States Geological Survey published a fact sheet that summarized its fundings on increasing nitrate concentrations in Barton Springs. Nitrates are a nutrient that can cause blooms of algae when present in excessive concentrations. When the algae dies and decomposes, dissolved oxygen in the water is used and levels of oxygen can become so low that fish and other organisms in the aquatic ecosystem cannot survive. The USGS found that nitrate concentrations in Barton Springs and the five streams that provide most of its recharge were much higher from 2008-2010 than before 2008. It also found that biogenic nitrogen from human wastes is the probable source. On Onion Creek, nitrate levels were six to 10 times higher than measured previously. Since 2001, the entire Barton Springs contributing zone has undergone tremendous development, and the number of septic tanks and discharges of wastes have exploded. You can get the fact sheet here. In October of 2018 the pool was closed due to sediment that made the water excessively cloudy. The source was traced to the drilling of a well, and the city issued a stop work order and a citation. Chris Mullins, staff attorney for the Save Our Springs Alliance said "We see something like this as more proof that Save Our Springs isn't done with our mission of protecting Barton Springs and what's really the crown jewel of Austin." Daily discharge measurements since 1978 show that flows from Barton Springs are rarely less than 10 million gallons per day and rarely exceed 80. Flows can vary widely depending on recent weather conditions and can drop rather quickly when dry conditions prevail. The USGS considers these records to be of poor quality, because the operation of the swimming pool can significantly effect the level seen by the water-stage recorder. As with all USGS stations, flow is determined by developing a relationship between water level and discharge. Since the pool is periodically drained for cleaning, there are times when the gage height is not in direct relation to discharge. Some of the precipitous drops and sudden peaks in the chart reflect pool operations, not changes in flow rate. For the latest real-time measurements, visit the USGS page for Barton Springs. For additional information on Barton Springs visit the Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer Conservation District.

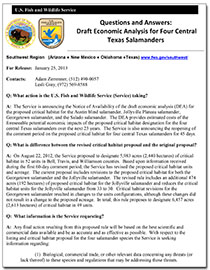

New Endangered Species Listings On August 22, 2012, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed to list four central Texas salamanders as endangered, the Austin Blind Salamander, Jollyville Plateau Salamander, Georgetown Salamander, and the Salado Salamander. It also proposed to designate 5,983 acres of critical habitat in 52 units in Bell, Travis and Williamson counties. Critical habitat is a term in the Endangered Species Act that identifies geographic areas containing features essential for the conservation of a threatened or endangered species, and which may require special management considerations or protection Based upon information received during the first 60-day comment period, in January of 2013 the Service proposed to revise the proposed critical habitat units and acreage. In addition, the revised proposal includes an amended Required Determinations section, an amended Exclusions section and the availability of a refined Impervious Cover Analysis. The current proposal revises the proposed critical habitat for both the Georgetown Salamander and the Jollyville Salamander. The revised rule includes an additional 474 acres of proposed critical habitat for the Jollyville Salamander; however, the numbers of critical habitat units for the Jollyville Salamander are reduced from 33 to 30. Critical habitat revisions for the Georgetown Salamander include adjustments to the critical habitat boundaries which does not change the overall proposed acreage. In total, this rule proposes to designate 6,457 acres (2,613 hectares) of critical habitat in 49 units. When specifying an area as critical habitat, the Endangered Species Act requires the Service to consider economic and other relevant impacts of the designation. If the benefits of excluding an area outweigh the benefits of designating it, the Secretary of the Interior may exclude an area from critical habitat, unless that would jeopardize the existence of a threatened or endangered species. So the Service also released a Draft Economic Analysis that quantifies economic impacts of the four central Texas salamanders conservation efforts associated with these categories of activity: development, water management activities, transportation projects, utility projects, mining and livestock grazing. The Draft Economic Analysis estimated impacts for development, transportation, mining and species and habitat management activities. No impacts are forecasted for water management activities, utility projects and livestock grazing activities. Total present value impacts anticipated to result from the critical habitat designation of all units for the four central Texas salamanders were deemed to be approximately $29 million over 23 years. All incremental costs are administrative in nature and result from the consideration of adverse modification in section 7 consultations and re-initiation of consultations for existing management plans. The Service also reopened the public comment period on the proposed listings and the revised critical habitat proposal and accepted public comments through March 11, 2013. You can get the draft analyses below:

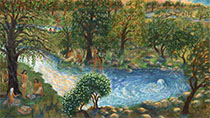

In August of 2013, two of the species were listed: The Austin Blind Salamander was listed as endangered, and the Jollyville Plateau Salamander as threatened. The Austin Blind Salamander is found only in and around the Barton Springs pool, and counts have never exceeded 1,000 individuals, but the listing was not expected to force closure of the pool. The city will be required to keep a Habitat Conservation Plan on file with the Fish and Wildlife Service that protects both the Austin Blind Salamander and the previously listed Barton Springs Salamander. The Service also announced the other two species being considered for listing would be studied for another six months before a decision would be made. In February of 2014, it announced the two other species would be listed as threatened, not endangered. Austin Field Office supervisor Adam Zerrenner said "The service's decision to list these species reflects the best available science and a careful evaluation of the comments received from the public." The Fish and Wildlife Service also proposed a special rule for the Georgetown Salamander that “would allow development activities to continue if they are in compliance with ordinances adopted in December by Williamson County and the City of Georgetown to protect water quality. These ordinances include steps to reduce contamination from spills and establishment of buffer zones around the species' habitat.” In September of 2018 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service finalized and issued a 20-year Incidental Take Permit to the Barton Springs Edwards Aquifer Conservation District that requires implementing a Habitat Conservation Plan for Managed Groundwater Withdrawals from the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer. Incidental Take Permits can be issued under Section 10 of the Endangered Species Act and they authorize the permit holder to "take" endangered species while conducting otherwise lawful activities. In this way, permit holders can proceed with activities such as construction or other economic development that may result in the "incidental" taking of a listed species. Such permits always require conservation measures, such as those outlined in the District's Habitat Conservation Plan. In theory, the Permit the Plan will ensure a sustainable use of the Aquifer and survival of the salamanders. Time will tell. You can download a copy of the permit and a copy of the plan here. In January of 2019 the University of Texas at Austin released a study that showed 13 central Texas salamanders are in danger in extinction due to overexploitation of groundwater. These include three at Barton Springs: the Austin Blind Salamander, the Jollyville Plateau Salamander, and the Barton Springs Salamander. The study relied on samples collected since the mid 1980s. In an interview for The Daily Texan, reseach fellow Thomas J. Devitt said urbanization has caused a decrease in the salamander populations. He said "Central Texas has some of the fastest-growing cities and counties in the nation, putting a strain on natural resources, especially water, and the environment. Overpumping of groundwater has caused (aquifer water levels) to drop and springs to stop flowing. This causes habitat loss for the salamanders." In June of 2019 an environmental group, the Center for Biological Diversity, filed a lawsuit against the Fish and Wildlife Service, claiming federal officials are failing to protect the Georgetown and Salado salamanders. The group alleges the federal government has not taken steps to protect the habitats of the two salamanders since they were first listed as threatened in 2014. Barton Springs - a Long Prehistory Barton Springs has a record of human history stretching back at least 10,000 years. Like all of the Edwards Aquifer springs, they figured prominently in native American culture and had great significance on many levels. Hundreds of generations of people carried out countless everyday activities such as cooking and gathering, and the Springs also had great significance on a social and sacred level. Archaeologists suspect that a megadrought which occurred between 3,000 and 6,000 years ago forced tribes that had previously inhabited the trans-Pecos region to make greater utilization of the reliable water sources along the Texas "Spring Line" - the Balcones Escarpment corridor that parallels I-35 and contains most of the major Edwards springs, including Comal Springs and San Marcos Springs (Tomka, 2011). One aspect of the increased utilization of the Springs involves a 4,000 year old cave painting in the Lower Pecos region of southwest Texas known as the White Shaman panel. Natives believe the painting depicts Barton and other Edwards springs as part of a sacred geography, and the panel is nothing less than the earliest map of Texas. One of its functions was serving as a guide for a sacred pilgrimage that people would endeavour to undertake at least once in their lives. In 2014, artist Susan Dunis created a series of paintings for these pages that depict a family of Lower Pecos natives on this sacred pilgrimage. Each painting illustrates a different aspect of cultural importance of the Edwards springs sites. This painting, the first in the series, depicts Barton's Upper Spring, which still flows as a fountain when pressure in the Aquifer is high. For the younger persons on the voyage, this is the first fountain spring they have seen, and it elicits a sense of wonder and awe. The older travelers greet it like an old friend. If you have seen Upper Spring flowing at fountain stage, whether just once or many times in your life, you have no doubt experienced the same feelings as those ancient persons. You are therefore bonded in spirit directly to those persons of 40 centuries ago.

The earliest known excavations along Barton Creek were conducted in 1929 at Barton Springs by J. E. Pierce of the University of Texas at Austin (Pipkin and Frech, 1993). In a letter to a colleague, Pierce wrote:

The Historical Period The numerous entradas, or formal expeditions, made by Spanish explorers between 1709 and 1722 undoubtedly encountered the ancient thoroughfares that cross-crossed the Texas landscape. These were made by migratory herd animals and the native Americans that pursued them. An old Comanche Indian trail from Bandera county to Nacogdoches passed Barton Springs (Brune, 1981). In 1730, Spanish missionaries chose a site for a mission near present day Zilker Park, but it was occupied for less than a year before the friars moved on to the previously established missions in San Antonio. Its exact location has never been determined. In 1821, the territory came under the control of the Mexican government, which opened up the land to colonization by foreign immigrants. Anglo pioneers began to pour into the region, acting on the Mexican government's promise of 177 acres of farmland and an additional league (4,428 acres) for each family. In 1837, William Barton and his family settled at the springs that would later bear his name. At the time, his nearest neighbor was Reuben Hornsby, eleven miles away at Hornsby's Bend. Barton had settled nearly 10 years earlier with Stephen F. Austin's colony in Bastrop, but when another family moved within earshot, Barton decided to pull up stakes and move upriver to a more private spot (Pipkin and Frech, 1993). Barton built a cabin on the bluff overlooking the present day swimming pool, and named the three springs grouped near his cabin after his daughters, Parthenia, Eliza, and Zenobia (the names never stuck, except for Eliza). If Barton sought solitude, he picked the wrong place, because others had designs on the sleepy little town of Waterloo, which lay just across the river. The Republic of Texas had achieved independence a year earlier (remember the Alamo?) and it soon began a search for a new capital city. A survey committee picked the town of Waterloo. In a letter to Mirabeau B. Lamar, the selection committee praised nearby Spring Creek, which afforded "the greatest and most convenient flow of water to be found in the Republic." Barton's springs began to supply the new city, and in December 1839 he agreed to "give possession of stream of water from my Big Spring" to furnish power for a sawmill. He died four months later, before the mill was built. The Springs became a popular site for picnicking, fishing, and swimming, and they were also the primary source of water for many local families. The property changed hands several times, first to Captain John J. Grumbles in 1855, then to John Rabb in 1860, and then to Jacob Grist, who purchased separate portions in 1866 and 1889. In 1901, Andrew Jackson Zilker purchased Barton Springs and 350 acres surrounding them. When droughts ravaged central Texas between 1910 and 1917, the practical need for drinking water gained attention from city leaders, and a military camp proposed for Austin at the time also stipulated a guaranteed water supply. Barton was a staunch advocate of manual-skills education, and he gave the city the tract containing Barton Springs on the condition the city would give $100,000 to the Austin School District earmarked for manual training at Austin High School. Before he died in 1934, he granted additional acreage that is now Zilker Park to the city, once again in return for funds dedicated to manual training (Pipkin and Frech, 1993). During World War I, army troops were stationed in Zilker Park and they used Barton Springs as a bathing area. Large baptismal ceremonies attended by hundreds were frequent events. There was no dam creating a pool as exists today, and Barton Springs lifeguard Ed Barlow reports that in the early 20s, they would pile up rocks each spring and use moss to plug the holes, which brought the water up so people could swim (Barlow, 1993). In 1922 the Chamber of Commerce and the Lions Club built a permanent bath house at a cost of $8,000. They began charging 10 cents, but you could easily slip in on the other side of the pool without paying (Kooch, 1993). That same year, construction started on the Barton Springs dam and an enlarged pool. In 1928 the firm of Koch and Fowler produced a plan for the city of Austin that advised "playgrounds and recreation facilities are as much a necessity to the health and happiness of people as are its schools, sewer systems, water supply, pavements, and drainage." The next year, a $30,000 improvement project was proposed. On September 23rd the Austin Statesman wrote:

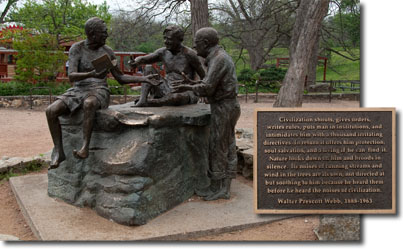

By 1936, the array of activities available in Zilker Park included swimming, horse-back riding, camping, tennis, shooting, boating, and dancing. Water pageants and music events were held throughout the spring and summer. Almost every day, an intellectual circle led by two legendary Texas writers, naturalist Roy Bedichek and folklorist J. Frank Dobie, would meet for discussion and contemplation at the limestone shelf next to the diving boards. They were occasionally joined by historian Walter Prescott Webb. This became known as The Rocksitters Era, and the rock became variously known as the Philosopher's Rock or Bedicheck's Rock.

Throughout the 1940s and 50s, Barton Springs remained an essential destination for many Austin residents. Austin and Barton Springs were Texas' best kept secret. It was a lovely place that seemed to have found the right balance between protection of natural resources and development. It was largely taken for granted that Barton Springs would always be there. But in January of 1961, stunned Austinites woke up one morning to learn that Austin's natural beauty had suffered a fatal catastrophe, a major fish kill in Town Lake. Over the next three weeks, a wave of poisonous substances moved downstram and killed almost every fish in the Colorado River between Austin and the Texas coast. It was found that a chemical plant had been routinely disposing of insecticides like DDT and chlordane into a storm sewer for over 10 years. The kill was triggered when high-pressure flushing of the storm sewers released a mass of toxins. Traces of chemicals can still be found in the sediments of Town Lake to this day. In 1962 this event was detailed by Rachel Carson in Silent Spring, the book that started the modern environmental movement.

In 1970, responding to the first threats of major construction on Barton Creek, the Austin Environmental Council filed a class-action suit seeking to declare Barton Creek a navigable waterway open to the public for recreational uses. In a time before the Clean Water Act, such a suit was one of the only tools available to preserve creeks. Around the same time, several landowners began negotiations to sell property along Barton Creek either to the city or to developers. The city turned down an offer to buy the property where apartments loom over Barton Springs today, and it also passed on many golden opportunities to purchase thousands of acres upstream in the Barton Creek watershed that is now densely developed. Today, Austin's natural beauty is a shadow of its former self, and the future of Barton Springs seems dim. Texas is struggling to find the right balance between protection of common resources and private property rights, and currently the pendelum is swinging strongly in favor of landowners, not residents.

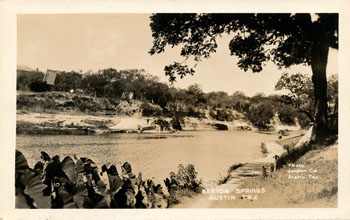

Some Barton Springs photos

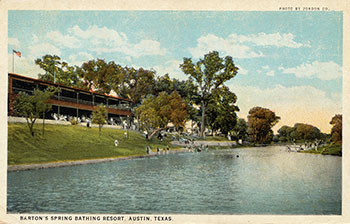

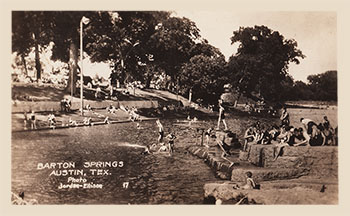

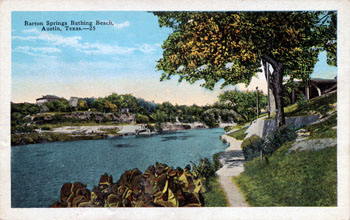

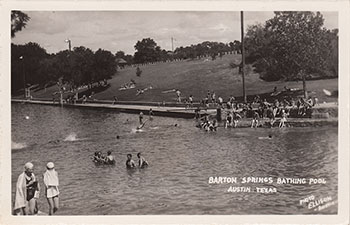

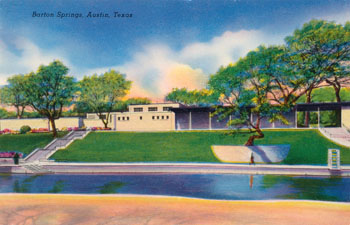

Postcards from Barton Springs Compared to other Edwards springs like San Pedro and San Marcos, there are not too many Barton Springs postcards out there.

A new bath house at the Springs was completed in 1922. It was a two-story pavillion with a dance hall upstairs and dressing rooms downstairs, and people recall it as quite romantic, with wood paneling and open-air screens (texasescapes.com, 2010). The first bath house was just four walls open to the sky and is reported to have been in use as early as 1884.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||