|

|

Laws and Regulations Applicable to the Edwards Aquifer For the Edwards, there are two primary issues that must be addressed by laws and regulations: 1) quantities of water pumped, and; Regarding pumping, over 100 years of litigation and court decisions have only partially resolved the battles over who owns, controls, and uses Edwards Aquifer water. Regarding water quality, the issue has barely been addressed and will likely take many decades to resolve. Many of the stumbling blocks on the path toward management of the Edwards were set in place by several fundamental flaws in Texas water law. These flaws are a legacy of Texas having been ruled by six different legal codes since Spain first claimed the territory in 1519. In most states and in most other nations, both groundwater and surface water are owned by the government. Laws and regulations that govern their use recognize that groundwater and surface water are all the same water. This is not the case in Texas. One of the main flaws in Texas water law is that groundwater is treated as if it were completely separate and different from surface water. To early settlers and governors, the existence and movements of surface waters were pretty obvious, so it was pretty straighforward to make laws regarding their use. Groundwater was different. Nobody really understood how or why groundwaters occurred or moved. In 1904, the Texas Supreme Court agreed with an 1861 ruling in Ohio that the existence and movements of groundwater were “so secret, occult, and concealed that an attempt to administer any set of legal rules in respect to them would be involved in hopeless uncertainty, and would, therefore, be practically impossible.” As a result, lawmakers declined at that time to make any laws regarding use of groundwater in Texas. Today, hydrogeologists don’t know everything, but we do know that surface water and groundwater are interconnected and inseparable. Even so, for over a century this "separation myth" has been a major impediment to the development of an integrated and conjunctive body of water law in Texas (Kaiser, 1987). For the most part, we are still living with the mistaken idea they are separate resources and over time, divergent regulatory schemes developed for the two. Even though it's all the same water, the differences in how surface water and groundwater are owned and regulated in Texas are profound. Surface water is the property of the State and its use is highly regulated. To use surface water, one must apply for a State permit and rights are assigned based on a "first in time, first in right" method. Such use does not necessarily convey ownership, and many cities are required to return certain portions to the stream after use. Regarding ownership of groundwater, the courts did not rule definitively until 2012 that it is the property of whoever's land it is under, but it was always treated that way nonetheless and there were very few regulations regarding its use, which was governed by the other main flaw in Texas water law, the "rule of capture". This rule was adopted by the Texas Supreme Court in 1904 in a case called Houston & T.C. Railway Co. v. East (the East case), in which the judges quoted the ruling in the 1861 Ohio case. In the East case, Mr. East had sued the railroad because it had drilled a large and deep well to supply locomotives and a machine shop, which caused Mr. East’s well to go dry. He sued and lost. The court ruled that landowners may capture as much water as they desired, without liability to surrounding landowners who might claim that pumping has depleted their own wells. The rule of capture is also called the "law of the biggest pump", because anyone can pump as much water from under their land as they like, as long as they put it to a beneficial use. So, just one person could use ALL of the Aquifer water if they could pump it out and put it to use. This was painfully pointed out to the entire region when Ronnie Pucek opened a fish farm in 1991 and began using as much water as one fourth of all the people in San Antonio. It became clear we had a situation in which everyone had infinite rights to a resource that was, in fact, finite. We had more "rights" than we have water.

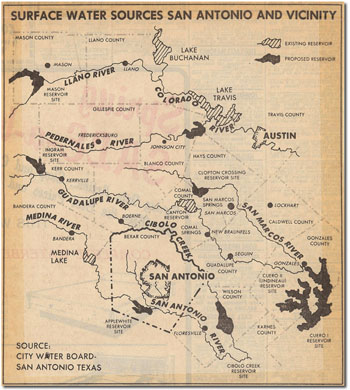

As a result of the ruling in the East case, landowners in Texas generally cannot protect themselves from harm caused by larger and deeper pumps, but over the years the courts have developed several exceptions to the rule of capture. Malicious pumping for the purpose of harming a neighbor is not allowed, causing land subsidence is not allowed, and drilling a slant well that crosses adjoining property is not allowed. Pumping water for wasteful purposes is also not allowed, but in practice, the courts have not placed limits on wasteful exploitation of groundwater. For example, in the 1955 case City of Corpus Christi v. City of Pleasanton, the Supreme Court refused to find waste even though 10 million gallons of groundwater per day was lost to evaporation and bank seepage while being transported through surface channels. Very little water was put to beneficial use, but that did not matter to the court. The fact that the law does not recognize any connection between surface water and groundwater only complicates matters when it comes to allocating State-owned surface water flows for private use. This is a bit of a side-issue to the rule of capture, but it's one worth exploring briefly because it gives us a sense of the difficulties that arise when interconnected resources are administered separately. What happened was this: as use of groundwater from the Edwards became greater over time, water that used to emerge at springs to become State-owned surface water was pumped from private wells instead. Many wells were allowed to flow freely, contributing large amounts of water to surface flows in the San Antonio River. In 1936, the USGS decried this practice in Water Supply Paper 773B, noting that many large buildings downtown used private wells for once-through cooling water in air conditioning towers, some as much as 10 million gallons per day. Flowing wells including the Farmers Well on Salado Creek contributed another 10-15 million gallons per day. By 1951, the USGS chief in San Antonio estimated that 48 million gallons per day were flowing down the San Antonio River from artesian wells. About this time, the wastewater treatment plant in San Antonio also began discharging treated water to the River (it had mostly been used in irrigation up until that time). The complication arises from the fact that unlike surface water, Texas law affords an absolute right of ownership over privately developed groundwater, and State allocation schemes did not account for the large amount of flow in the San Antonio River that began to be derived from private wells and wastewater plants. In State models, these flows were included as part of the "naturalized" flow, which is supposed to represent the flow that would be in the River without the influence of man. So for decades, the State went about assigning surface water rights to people whose water may have originally originated as springflow, but now originated from artesian well flows or wastewater plants. Today, almost all of the flowing artesian wells have since been plugged or controlled, the springs in San Antonio rarely flow, and a large percentage of the flow in the San Antonio River during very dry times comes from the city's wastewater discharges. Together, the flaws in the State's modeling, the elimination of free-flowing wells, and the reliance on wastewater discharges for dry-weather flow combine to form a potential problem for surface water rights holders. People who have been granted surface water rights might not have any water during low-flow times if San Antonio decides to reuse all its wastewater instead of discharging it downstream. Because San Antonio owns its groundwater, it has no legal obligation to release any to meet downstream demands. And there also might not be any water to maintain flow in the San Antonio River, which has immense value both for the environment and regional economies that depend on fishing, tourism, recreation. Although San Antonio has become very proactive in developing uses for its treated wastewater, it has also so far remained committed to environmental stewardship and releasing water to help support downstream economies and ecosystems in the San Antonio River and San Antonio Bay. Even though it doesn't have to, the city has sought to strike the proper balance between reuse, environmental protection, and supporting regional economies. For our discussion, it's important to note this has occurred not because of a legal or regulatory framework but in spite of it, simply because San Antonio stepped up voluntarily to do its part. But back to the rule of capture. Despite all its flaws and complications, the rule of capture can work ok as long as there is enough water for everybody. But it wasn't too long after the East case that people began to realize there may not be enough to go around. In 1917, following a period of severe drought, the people of Texas adopted section 59 of the Texas Constitution, the Conservation Amendment. This Amendment declared "the responsibility for the regulation of natural resources, including groundwater, rests in the hands of the Legislature." However, many efforts to pass a comprehensive, statewide groundwater management scheme failed, and more than three decades elapsed until the state passed the first significant legislation providing for the conservation and development of groundwater. Now Chapter 36 of the Texas Water Code, the Groundwater Conservation District Act of 1949 permitted landowners to petition for creation of a groundwater conservation district to regulate production from an underground reservoir. Then came the 1950s and the worst drought on record in Texas, and it became clear that water supplies were inadequate to support future projected growth. Numerous water planning studies were undertaken but little progress was made toward management of the Edwards Aquifer or toward development of other water resources. As a response to the 1950s drought, the Edwards Underground Water District was created in 1959 and it was charged with conserving and protecting water in the Aquifer. However, it had no authority to restrict groundwater pumping, and for over 30 years it was mainly a data collection agency. In 1961, the State released the Texas Water Plan that discouraged over-reliance on the Edwards and recommended several new reservoirs, of which only Calaveras Lake was ever constructed. An update to the 1961 plan was produced in 1966, with a final version in 1968, and it outlined an ambitious program of additional statewide reservoir construction with those around San Antonio being in Phase I. Reservoirs to meet San Antonio’s needs were the Cuero I, Cuero II, Goliad, Cibolo, and Cloptin Crossing. None of them were ever built. The most significant contribution of the 1968 Texas Water Plan was the determination that based on historical rates of recharge and discharge, withdrawals from the Edwards should not exceed 400,000 acre-feet per year. As we shall see, this number stood the test of time, at least until 2008. In addition to the eye-opening fish farm that opened in 1991, another development in that year turned out to be a turning point in Aquifer management. In May of 1991, the Lone Star Chapter of the Sierra Club filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service claiming the Service was not adequately protecting endangered species that depend on the Aquifer. The Sierra Club argued that Comal and San Marcos Springs could dry up if unrestricted pumping continued and that would constitute a "taking" as defined by the Endangered Species Act. The Sierra Club asked that the Service be required to ensure minimum springflows to protect the endangered species. After a two year trial, in January 1993 Federal Judge Lucius Bunton of the U.S. District Court in Midland ruled in favor of the Sierra Club and others who had joined the suit along with the Club. The court found that if unrestricted withdrawals continued, endangered and threatened species would be "taken" as defined by the Act. The court also found the Fish and Wildlife Service had failed to implement a recovery plan for San Marcos and Comal Springs and had caused risk or jeopardy to the endangered species. Judge Bunton ordered that springflow must be maintained even during a drought like in the 1950s. He directed the Texas Water Commission to prepare and submit a plan to ensure springflows, and he directed the Service to determine springflow levels that would result in "take" or "jeopardy" of the species. The Service subsequently determined that level was 150 cubic feet per second at Comal Springs; however, a study commissioned by the Service and leaked in May 2000 predicted that even at flows as low as 30 cfs, 60% of the fountain darter's habitat would be maintained (see news article). Another technical evaluation completed in 2009 by Dr. Thomas Hardy concluded that species at Comal Springs could withstand flows as low as 30 cfs for up to six months, and at San Marcos Springs 45 cfs would be protective for six months (see the study). Hardy's evaluations had far-reaching impacts that eventually gave regional officials more options than simply cutting back use dramatically when flows at Comal and San Marcos Springs decline, but we are getting ahead of the story. In the 1993 ruling, Judge Bunton also announced the Texas Legislature had to enact a regulatory plan to limit withdrawals from the Aquifer or he would implement his own plan, which would mean the federal government would be in charge of the Aquifer. In cases like this, the federal government is usually willing but reluctant to exert control if matters can be handled effectively by local governments. So the state of Texas was given a chance to act in order to defer federal intervention, and in May 1993 the Texas Legislature passed Senate Bill 1477, which replaced the Edwards Underground Water District with the Edwards Aquifer Authority. The Bill authorized the new agency to issue permits and regulate groundwater withdrawals from the Edwards. It essentially ended the rule of capture in the Edwards region and it laid out the legal framework for assigning permanent water rights to people who had been using it for many years. The bill also created means to market groundwater rights by making permits transferable (with some restrictions), and it set a cap on permits at 450,000 acre-feet annually, to be reduced to 400,000 acre-feet in 2008, the number identified in the 1968 Texas Water Plan. It also provided for short term permits for additional use when rainfall and recharge are high, required the Authority to adopt a Critical Period Management Plan to reduce pumping during droughts, and addressed the question of preserving endangered species habitats by requiring the Authority to provide continuous minimum springflows. In August 1993, before the new agency could be seated, the U.S. Department of Justice put the legislation on hold because it wanted to determine if the new law violated the Voting Rights Act by replacing the elected Board of the Edwards Underground Water District with an appointed board of the new Edwards Aquifer Authority. In November 1993, the Justice Department ruled that SB 1477 did indeed violate the Voting Rights Act. This was remedied in June 1995 when the Texas Legislature passed House Bill 3189, which provided for an elected Authority board. On June 28, 1996, the Authority began operation with an interim, appointed board, and an election to replace interim board members with elected members was held in November 1997. Today, the Authority has the power to manage, conserve, preserve, and protect the Aquifer, increase recharge, and prevent waste. If the federal courts feel the Authority is not effectively doing these things, there is still the chance the federal government could step in and take control. The new Authority set about the process of establishing rules by which the goals of SB 1477 would be met and pumping demands on the Edwards reduced. Initial regular permits were to be issued by the Authority based on historic use from the Aquifer from 1972 to 1993. Over 1,000 applications were filed, and the total amount of water applied for was 832,244 acre-feet, far more than the 450,000 acre-feet cap. The Authority had the difficult job of deciding who got how much. Meanwhile, several challenges to the new rules were issued, and the Authority’s rules ended up being invalidated twice. In one case, the Living Waters Artesian Springs (the catfish farm) sought an injunction against processing of the applications. It claimed the rules were adopted in violation of the Texas Administrative Procedures Act, which requires reasoned justification in writing before rules can be adopted. In December 1998, all the Authority’s rules that had been adopted up to that time were held to be invalid. In another challenge two pecan farmers from Medina county, Glenn and JoLynn Bragg, filed a suit under the Texas Private Real Property Rights Preservation Act, claiming the Act required the Authority to perform a Takings Impact Assessment (TIA) before adopting rules and issuing permits. Basically, the argument was the Authority had not adequately assessed the impact of what it was doing. Judge Mickey Pennington ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and again invalidated the Authority’s rules. After having all its rules invalidated twice, the Authority began working very hard to do whatever necessary to come up with a "bulletproof" set of rules that could survive all legal challenges. The Authority spent almost a year following the process outlined in the Texas Administrative Procedures Act which includes assessment of the impact of rules on small businesses, government entities, and the public. In January 2000 the Authority got a boost when an appeals court ruled that Judge Pennington erred in deciding the rules were invalid because they violated the Property Rights Preservation Act. Final Rules were adopted by the Authority in late 2000. On January 9, 2001, the first permanent Edwards Aquifer pumping permits were issued. It was a major milestone for management of the Edwards Aquifer. Members of the Stein family, who drilled one of the first irrigation wells in Medina county, were handed the first permit to pump 224 acre-feet from the Aquifer each year. Overall, 308 permits were issued granting rights to 133,186 acre-feet, about a third of the volume the Authority was authorized to allocate. More final permits were issued in February 2001, leaving about 250 contested permits to be sorted out in court.

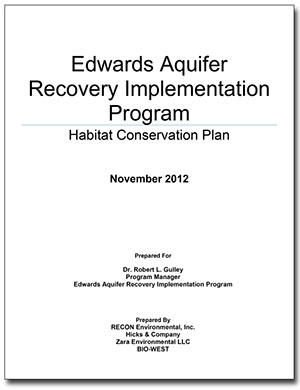

In February 2002, the Texas Supreme Court issued a landmark decision that affirmed the Authority's powers to regulate pumping. In an appeal of the Bragg case, the court ruled the Property Rights Preservation Act has an exception for regulating groundwater, and the EAA need not prepare a Takings Impact Assessment before adopting rules. The 1994 legislation that established the Edwards Aquifer Authority included conflicting provisions regarding total pumping and issuance of rights. These conflicts were not resolved until 2007. The agency was required to limit pumping to 450,000 acre-feet per year by 2004, and to reduce pumping to 400,000 acre-feet by 2008, but it was also required to issue minimum annual pumping rights to users who could prove their use during the prior 21 years. As mentioned above, initial claims were far in excess of 450,000 acre-feet. After failed attempts in two legislative sessions to address the problem, the EAA attempted to resolve the issue on its own in December of 2003 by creating a class of interruptible rights. The Authority designated about 10% of most pumping permits as "junior rights" which could not be used if Aquifer levels dropped below certain triggers. In January of 2007 this scheme was dealt a serious blow when Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott issued an opinion that concluded the Edwards Aquifer Authority did not have the statutory authority to reduce the withdrawal rights of permit holders or issue interruptible "junior" withdrawal rights. EAA officials said they didn't consider themselves bound by the Attorney General's opinion and would seek to have the legislature ratify the junior/senior permitting scheme by statute. Later in 2007, the Legislature did indeed finally address the issue, but not by ratifying the EAA scheme. Over the objections of environmentalists and regional entities like the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority, the legislature raised the pumping cap to 572,000 acre-feet. Also in 2007, the Texas Legislature directed the EAA and other state and municipal water agencies to participate in a collaborative, consensus-based stakeholder process to finally develop a plan to protect the federally-listed species dependent on the Edwards Aquifer. This was to be known as the Edwards Aquifer Recovery Implementation Program (EARIP). Developing such a plan was one of the initial responsibilities given to the EAA by Senate Bill 1477 when it was created in 1993, but it was never able to come up with a plan that could gain regional support and pass federal muster. The idea behind the Legislature's 2007 directive was that if you take a bunch of people who have never agreed on anything and lock them in a room together for four years, they will become friends. Or at least learn to get along. The group was given a 2012 deadline for preparing a Habitat Conservation Plan that stood a chance of being approved by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. An approved plan would result in the issuance of a federal "Incidental Take Permit" under Section 10 of the Endangered Species Act, which authorizes permittees to "take" endangered species while conducting otherwise lawful activities. In this way, permit holders can proceed with activities such as construction or other economic development that may result in the "incidental" taking of a listed species. Without an approved plan in place, or if an approved plan fails to adequately protect the endangered species, it is still possible that water management in the region could fall into the hands of a federal judge. The Legislature directed that the EARIP Plan must include recommendations regarding withdrawal adjustments during critical periods that ensure the federally-listed species associated with the Edwards will be protected. By mid-2010, the EARIP group was considering a package of options that ranged from recreation management to large scale engineered solutions like Aquifer Storage and Recovery and Recharge/Recirculation schemes. In January 2011, the group reached a consensus about the elements and financing for a plan. The cost would be about $30 million per year, about half of which would go to the San Antonio Water System to use a portion of the storage capacity at SAWS’ Twin Oaks Aquifer Storage and Recovery facility to augment flows during dry times. Another $10 million would go to farmers not to irrigate, and the remaining $5 million would go to improving habitat, conservation programs, and scientific studies. To finance the plan, the EARIP members agreed the fairest approach would be a new ¼ cent sales tax imposed in counties within the jurisdiction of the EAA and in the watersheds of the Guadalupe and San Antonio rivers. This would ensure that all who benefit from the Edwards pay some portion for its protection. Some officials such as Senator Leticia Van de Putte expressed support for the idea but were skeptical that it could receive approval. The skeptics were right – the political climate in the 2011 legislative session revolved around anti-tax/anti-government sentiments, and Governor Rick Perry vowed to veto any new tax bill that reached his desk. Even though an equitable funding solution was not politically possible, the EARIP members final plan had to include a funding mechanism or it would be unlikely to receive U.S. Fish and Wildlife Department approval. To address the funding problem, the EARIP members had little choice but to propose higher fees on pumpers. Fees for agricultural pumpers are capped by law at $2 per acre-foot, so the burden had to be placed on industrial and municipal pumpers. Under the EARIP proposal, fees for industrial and municipal pumpers would rise from about $36 per acre-foot to as much as $116 per acre-foot. Most of the cost would be borne by San Antonio, which holds the majority of municipal pumping permits. The final plan was submited to the Fish & Wildlife Service on January 5, 2012. The Service conducted a review, prepared a draft of both the plan and an Environmental Impact Statement, and both were released for public comment in September of 2012. Final approval was expected by the end of 2012, which came and went with no word. Finally, on February 14, 2013, notice was filed in the Federal Register regarding the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service's long-awaited final decision - to issue a 15-year incidental take permit to the EARIP for implementation of the Service’s preferred EARIP plan. The final Federal Register entry was published on February 15. The preferred and approved plan was assigned a date of November 2012 and includes a number of measures to maintain or manage springflow, including Critical Period Management pumping restrictions, use of SAWS’ Twin Oaks Aquifer Storage and Recharge facility to meet water demand that offsets reduced pumping from the Edwards Aquifer near the springs during drought, a Voluntary Irrigation Suspension Program that provides economic incentives to reduce pumping for irrigated agriculture during drought conditions, and a Regional Water Conservation Program. The approved plan also provides for habitat restoration and management measures that minimize and mitigate impacts from the potential incidental take to the maximum extent practicable. While many regional entities and interested citizens participated in the EARIP plan development, the applicants and permit holders are the cities of New Braunfels and San Marcos, the San Antonio Water System, Texas State University, and the Edwards Aquifer Authority.

Joe G. Moore, Jr. The linchpin of the Habitat Conservation Plan, the thing that makes it a viable solution for the region, is the inclusion of an Incidental Take Permit from the Fish and Wildlife Service. The idea for this came from Joe G. Moore, Jr., who was a true giant in the field of environmental protection. Moore wrote Texas' first water pollution control laws in the 1960s, served as executive director of the Texas Water Development Board and chairman of the Texas Water Quality Board, and then he went to Washington to serve as Commissioner of the Federal Water Pollution Control Administration. From 1973 to 1976, he was Program Director of the National Commission on Water Quality. Returning to Texas, he taught college for almost 30 years, instructing several new generations of water pollution control experts. In 1994 he was appointed by U.S. District Judge Lucius Bunton to serve as a court monitor to ensure that court directives were carried out in the wake of the Sierra Club lawsuit against the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. On behalf of Judge Bunton, he convened an Incidental Take Permit Panel, which he conceived as a means to arrive at a plan to ensure endangered species protection. The EARIP stakeholders that arrived at a regional consensus in 2011 simply finished what he started. Mr. Moore passed away in 2005 at his home in Austin, having set in motion the regional solution that is the Edwards Habitat Conservation Plan. In the video, Mr. Moore conducts the first meeting of the Panel and introduces the regional representatives, who were selected in consultation with the Court as persons responsible to the entities involved. The Day & McDaniel Case At the beginning of this essay, I mentioned the battle over who owns, controls, and uses Edwards Aquifer water has only been partially resolved. Until 2008, most believed that it had indeed been resolved. But in November of that year, the fundamental premise of Edwards regulation, the idea that landowners do not have the right to capture unlimited amounts of groundwater, was brought into question. Most believed the 2002 Supreme Court decision in the Bragg case affirmed the position that Edwards pumping could be regulated, and that people who didn't receive a permit didn't own any water. Since 2002, the EAA has proceeded to issue permits and allocate groundwater rights. But in 2008, several appeals court decisions clouded the picture. In the 4th Court of Appeals, Justice Steve Hilbig ruled that landowners involved in a lawsuit with the EAA have some vested ownership rights of groundwater beneath their land and their "vested right in the groundwater beneath their property is entitled to constitutional protection." The ruling, along with a similar ruling in a case in Del Rio, set up a Supreme Court showdown over the rule of capture and groundwater ownership in Texas. The case involved landowners Burrell Day and Joel McDaniel, who purchased land over the Aquifer and filed a permit application for 700 acre-feet, but were awarded a permit for only 14 acre-feet. They were unable to show historical use for the larger amount. They appealed, and also added constitutional claims they were entitled to 1,834.8 acre-feet, or two-acre feet for each of the 917.4 acres they own. They claimed that under the common-law rule of capture, they have a vested right to water, even though they never produced it or put it to a beneficial use, and the EAA committed a “taking” when it issued them a permit for less than they could pump in absence of regulation. In court briefings, the EAA outlined several reasons why the court should have affirmed there is no vested interest in groundwater prior to production and use. First of all, in the 1904 case that established the rule of capture as the law in Texas, the landowner lost. In that case, the landowner Mr. East had no ownership rights, only the railroad had any. So it is sort of a conundrum to argue in favor of vested water rights based on a case in which one party had none. Secondly, the right to exclude others is one of the most fundamental elements of a property right, and under the rule of capture, no one has the right to do so, therefore the rule of capture does not afford any vested rights. The EAA also pointed out that Day & McDaniel’s claim, if successful, would unfairly advantage landowners who had never used water over those who had invested money and sweat to make the water productive, since both would end up with rights of equal value. In other states and in England where the common-law rule of capture originated, courts have uniformly concluded that landowners do not own groundwater prior to its production and capture. In Texas, the courts encouraged the Legislature to take action to provide for meaningful management and regulation of Edwards water, and it did so by creating the EAA and assigning rights that gave preference to historical use. As early as 1955, justices noted the rule of capture was outmoded, since the movement of groundwater, which was previously thought to be mysterious and unknowable, was no longer so. As noted above, the court has modified and limited the rule several times to restrict malicious pumping and protect nearby landowners from subsidence. The court has also indicated on several occasions that it would abandon the rule of capture if Legislative solutions were unsuccessful at creating fair, effective, and comprehensive management of groundwater. In any case, there is simply not enough water to assign the typical allocation of two-acre feet per year to the landowner of every acre, and doing so would cause major disruption to cities and industries that are vital to the region and its population. After the Texas Supreme Court heard arguments in the case in February of 2010, the word from my knowledgeable sources on the street was the Court wasn't in any hurry to rule because it preferred the Texas Legislature address the issue. When the Legislature met in 2011, State Senator Troy Fraser filed Senate Bill 332, which specifically affirmed that landowners have “a vested ownership interest in and right to produce groundwater below the surface” of their land. As Texas is noted for its strong focus and support of private property rights, it seemed assured the bill would pass easily and be signed into law by the Governor. It did pass, and it was signed into law, but not before it was amended to include an exemption for the Edwards Aquifer Authority. So, a bill that was designed to address an Edwards Aquifer court case ended up not really doing so, and we all sat back and waited for the Supreme Court to finally rule. The court delivered its opinion on February 24, 2012, and it rejected all of the EAA's arguments. It ruled that land ownership includes an interest in groundwater in place that cannot be taken for public use without adequate compensation, and it remanded the case to the district court to decide if a taking occurred in this particular case. For the first time, the court definitively settled the question of ownership by affirming that groundwater is owned by the landowner. This does not mean, however, that regulation of pumping is totally out the window or that we will now return to the rule of capture free-for-all that prevailed in the catfish farm days, because the court also affirmed that pumping can be subject to limitations and regulations. The question is what manner and degree of groundwater regulation constitutes a compensable taking. This is always decided on a case by case basis based on the facts of each particular case, and whether or not a "taking" occurred is a matter of degree. For example, if you own a lot that is zoned for residential use, the court would be unlikely to rule that a taking occurred if the city denied your request to build a convenience store. But if the city wanted to take your lot to create a park and denied you of all the value of your property, that would very likely constitute a taking for which the city would have to provide compensation. In the Day & McDaniel case, the court did not rule on the question of whether a compensable taking occurred. But it did make a finding that raises questions regarding the application of EAA regulations to the Edwards. The court stated "a landowner cannot be deprived of all beneficial use of the groundwater below his property merely because he did not use it during an historical period and supply is limited." As we have seen, historical use was the basis of the EAA’s water rights allocation scheme. Even so, the court ruled the EAA properly followed the law in this case. If it is determined that a taking occurred, the question of appropriate compensation will also have to be decided. In most cases, compensation is based on the value of property before the taking. In the Edwards region, groundwater had very little value before pumping limits and regulations were enacted. Regulation and the issuing of permits is what created the market, and Edwards rights are now very valuable. So if there was a taking in this case, the value of what was taken could turn out to be very small. So, does this mean a new wave of additional lawsuits by other landowners who received permits for less than they applied for, or by landowners who did not apply at all? Will the financial burdens of such claims make regulation impossible? Will this disrupt the robust market that has developed in EAA permits in that buyers will be wary of paying for permits that may later be reduced? These are large unanswered question, and only time will tell. Many landowners may be reluctant to brings takings claims because they are always very difficult to prove, and the court also affirmed in the Day & McDaniel ruling that the loser has to pay all legal fees, which can be extremely expensive. One thing for certain is that we now have a great deal of uncertainty, which is never a good thing in the water planning business.

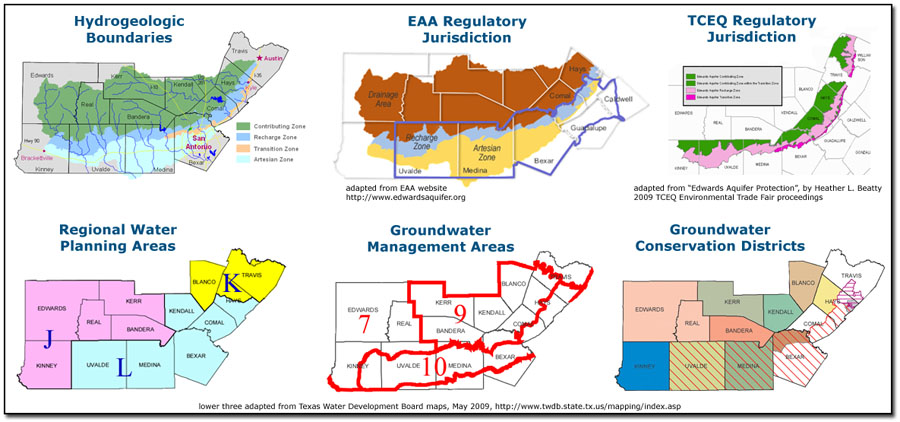

Groundwater Conservation Districts While the issue of potential takings claims looms large, the issue of protecting water quality looms even larger as one that remains unresolved. We will examine the issue of Edwards water quality in depth shortly, after we examine the evolution and current state of Groundwater Conservation Districts in Texas. At this juncture it is worth noting that ironically, a 1990s Supreme Court decision on the rule of capture served to complicate the issue of water quality protection by encouraging a new layer of governmental jurisdiction, in the form of Groundwater Conservation Districts, over areas that contribute water to recharge. As usual, let us begin with some history. More than 90 years after the East decision, the Texas Supreme Court reviewed a ruling in a case called Sipriano V. Great Spring Waters of America, et al. In this case, the owner of a domestic well claimed that pumping by the bottlers of Ozarka water had dried up his well, and he asked the court to protect his private property interest in groundwater by imposing liability on Ozarka. Many observers thought the Texas court would modify the rule of capture to protect rural homeowners and domestic users of water. They were wrong. The court unanimously affirmed the rule of capture. However, it left the door open for legislative restrictions by affirming that pumping groundwater within the jurisdiction of a Groundwater Conservation District (GCD) may be limited. As mentioned above, Groundwater Conservation Districts were first created in Texas in 1949. They are units of local government with locally elected boards that historically were focused mainly on developing and implementing conservation plans, not limiting pumping. By the late 1990s most politicians had come to recognize the rule of capture is basically an unworkable free-for-all, because it gives everyone unlimited rights to a finite resource. It is sort of like a circular firing squad. Even so, none had been willing to tackle the issue head on, and you can't really blame them. In Texas, politicians who dare to suggest that private property rights are less than paramount are routinely placed on rails and escorted from town wearing tar and feathers. So in 2001, in the wake of the Ozarka decision, and instead of tackling the issue head-on, the Legislature punted by passing a law that makes it easy for property owners to form Groundwater Conservation Districts (GCDs) by petition. It gave such Districts the authority to regulate spacing and production from wells, and deemed GCDs to be the State's preferred method of groundwater management. This provided a politically correct frame of "local control" for pumping regulations while allowing lawmakers to avoid certain political doom. Since 2001, the number of such districts has more than doubled to more than 120. All the Districts participated in a process in which local residents determined the "Desired Future Conditions" (DFCs) for their aquifer. A Desired Future Condition is a quantifiable future groundwater condition, such as a particular groundwater level, a level of water quality, or a volume of spring flow. Most of the time, the Desired Future Conditions will involve pumping limits. After Desired Future Conditions were established, it was then possible to use groundwater models to determine what is logically known as the "Modeled Available Groundwater," or MAG. This is the amount available for the Groundwater Conservation District to allocate through pumping permits. By 2014, several Districts were reporting they felt they would be unlikely to achieve their Desired Future Condition, even with only a portion of their Modeled Available Groundwater permitted. This is largely attributed to an increasing number of exempt wells. In most Districts, domestic wells and wells used for livestock are not required to be permitted, only registered. They are usually limited to having a capacity of 25,000 gallons per day. That is quite a lot of water when you consider that most families of four use half that amount in a month. All over the Hill Country, large ranches are being divided up into smaller ranchettes, with owners building large extravagant primary or secondary residences. Suddenly, there are 20 exempt wells on a tract where previously there was just one. All of this activity is having large implications for water supply and sustainability on the Edwards Plateau. While the issue of exempt wells looms large, it is perhaps only a secondary consideration in the larger issue of finding a holistic and integrated water management scheme for Texas' aquifers. The main issue is jurisdiction. While aquifers occur regionally, the boundaries of Groundwater Conservation Districts are almost always drawn along county lines, so areas outside of a Groundwater Conservation District that use the same aquifer have no voice in the process of defining DFCs. It almost goes without saying that GCDs are an inconsistent and fragmented approach to regulating a shared resource. On top of that, there are several additional layers of jurisdiction for planning and management and an array of confusing overlaps between all of them. For example, Groundwater Management Areas (GMAs) were designated by the Texas Water Development Board in 1995 to provide boundaries to encourage the cooperation of management agencies and research. There are three GMA's covering various portions of the Edwards region. In addition, Regional Water Planning Areas (RWPAs) were required by Senate Bill 1 in 1997 and are intended to provide a framework to develop a state water plan. Under the Planning Area process, the state is divided into 16 regions, and each is required to work on a 5-year cycle to identify future water demands and develop a plan to meet those needs. There are three RWPAs covering various other portions of the Edwards region. All of this creates a very challenging environment in which to try and manage water.

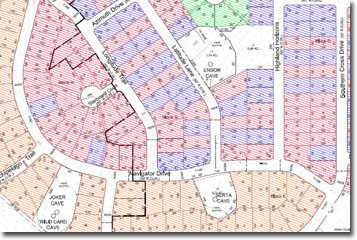

The Bragg Case In May of 2015 almost 18 years of litigation reached a decision point when the Texas Supreme Court declined to review an Appeals Court ruling in Edwards Aquifer Authority v. Glenn and JoLynn Bragg. It marked the first time that a landowner in Texas had a ruling that groundwater rights were taken by a groundwater conservation district. The decision clouded the future of regulated pumping in Texas, but the long term impacts may be far less significant for the Edwards region than for other areas in Texas. This is because of a 10-year statute of limitations on takings claims after an Edwards permit is issued. There are not many Edwards permits for which the clock has not already run out. For other groundwater districts, however, the decision may lead to litigation over existing permits and may have a chilling effect on their future permitting activities. The case involved water rights for two pecan orchards owned by the Braggs. In 1979 they purchased a 60-acre tract of raw land where they drilled an Edwards well, planted over 1,800 pecan trees, installed an irrigation system, built a barn, and made the site their home as the Home Place Orchard. In 1983, in order to make better use of equipment they purchased for the Home Place Orchard, they purchased the 42-acre D’Hanis Orchard, which had been planted with 1,500 pecan trees in 1979. Pecan trees can take decades to reach full maturity, and the Braggs told the court they believed their trees would eventually need about 600 acre feet of water per year. But the EAA’s allocation of groundwater rights was based on an applicant’s maximum beneficial use during a historical period from June 1, 1972 to May 31, 1993, and during that period the Braggs' pecan trees had not matured to the point where they required the amount of water that would be needed when they were fully grown. So the Braggs applied for water rights based on their use in 1996, well after the historical period. On their application for the Home Place Orchard, they claimed their maximum beneficial use was 228.85 acre-feet, and they noted “the Historical Use should not be applicable because trees require more water each year as they reach maturity.” For the D’Hanis Orchard, they applied for 193.12 acre-feet. They were granted a permit for the Home Place Orchard for 120.2 acre-feet, which the EAA based on their use from 1972 to 1993, and because the Braggs could not show any historical use on the D’Hanis Orchard, that permit was denied completely. In November of 2006, the Braggs sued the EAA for an alleged taking of their property and for violation of their federal civil rights. Although the suit was initially removed to federal court, a federal court judge dismissed the Braggs' civil rights claims and remanded the takings claims back to state trial court. The trial court found the Authority’s denial of the D’Hanis Orchard application amounted to a regulatory taking for which the Braggs were entitled compensation of $134,918.40, and the granting of a permit for the Home Place Orchard for less than the requested amount also amounted to a regulatory taking for which the Braggs were entitled $597,575 in compensation. The case was appealed to the Texas Fourth Court, which in August of 2013 affirmed the trial court’s ruling that the EAA violated the Braggs' private property rights when it limited their ability to pump water from underneath their land. However, it found flaws in the way that compensation was decided and it remanded the case back to the lower court to re-decide the issue of compensation owed to the Braggs. There were actually several issues the Fourth Court of Appeals had to sort out. The first was whether the Braggs had sued the right party. The EAA claimed the Braggs should have sued the State of Texas, not them. The judge concluded the State may have been a proper party, but so was the EAA. Secondly, the court had to decide on a statute of limitations issue. The EAA argued the Braggs’ takings claims accrued in June of 1996 and a 10-year statute of limitations had expired by the time they filed suit in November of 2006. The Braggs countered that their claims did not accrue until their permit applications were denied in 2004 and 2005, well within the 10-year limit. The judge agreed with them, noting that because the provisions of the law were not applied to the Braggs until 2004 and 2005, their claims were not time-barred. Finally, the court ruled on the issue of how compensation to the Braggs should be decided. For the Home Place Orchard, the lower court had applied a formula based upon the difference between the market value of the rights they requested and the rights they received. For the D’Hanis Orchard, the court determined the proper method was to calculate the difference between the market value per acre for a dry land farm and the market price for irrigated farm land. The Appeals court ruled these methods were erroneous and it remanded the case back to the lower court to try again. It concluded the “property” actually taken was the unlimited use of water to irrigate a commercial-grade pecan orchard, and that “property” should be valued with reference to the value of the commercial-grade orchards immediately before and immediately after the provisions of the law were applied to the orchards in 2004 and 2005. Although no one disputes that landowners should in many cases be compensated when regulatory takings of private property occur, it is the judge’s reference to this property as being the “unlimited use of water” that has caused regional consternation and uncertainty regarding the future ability of groundwater districts in Texas to regulate pumping. If on the one hand property values derive from the expectation that water use can be unlimited, while on the other hand groundwater districts are formed to regulate pumping, then these two hands are obviously in conflict. At the annual meeting of the Texas Alliance of Groundwater Districts, long-time water lawyer Mary E. Kelley said “Groundwater districts are facing an impossible task. I just don’t know what the districts do with this.” In comments provided to the Texas Tribune, SAWS legal counsel Steve Kosub said “What cannot be ignored is the fact that this judicial opinion represents a dramatic change in public policy in a particularly troubling context. If the government cannot reasonably regulate access to scarce water supplies without paying for every diminishment of value incident to property, then the future of 40 million Texans may be bleak indeed.” You can get the Appeals Court ruling here. When the Texas Supreme Court let the Appeals Court ruling stand, legal experts cautioned the Supreme Court's denial of review should not be read so broadly as to mean that groundwater districts cannot regulate groundwater. Takings cases are always very fact-specific, and while regulators may be more cautious than before the opinion, each potential case in the future would be reviewed based on the facts in that particular case. On the other hand, legal experts also saw the ruling as extremely favorable to the position of the Electro Purification firm, which is engaged in a controversy about pumping from an unregulated tract of land near Wimberley. Read about that case on the Trinity Aquifer page. In January of 2016, a mediation session was scheduled where parties tried to agree on the amount of compensation owed to the Braggs. The mediation failed, and the case was scheduled for a jury trial on February 16. On February 22, after hearing closing arguments, jurors deliberated throughout the afternoon and found that Glenn and JoLynn Bragg were owed $2,551,490 by the EAA for unconstitutionally taking their private property. In May of 2016, Judge Tom Lee of the 38th Judicial District Court awarded the Braggs compounded daily interest on their $2.5 million, adding $1.97 million to the total award. In July of 2016 the Board of the EAA voted unanimously to approve paying the Braggs $4.524 million. Legal experts noted that in the end, additional issues remain and uncertainty continues to exist. Because the Supreme Court let the appellate decision stand and did not weigh in on the issue, there is still a lack of direction from the highest court. As is stands, the appellate court's ruling seems to tip the balance toward landowners when faced with limits to their water use imposed by groundwater districts. Staff lawyers at Lexology, which provides legal analyses to business professionals, concluded that groundwater authorities should fear that landowners across the state will be encouraged to attack existing regulation on their pumping. They wrote "...landowners now have strong footing in the assertion that regulations limiting their ability to pump groundwater represent a "taking" that deprives them of their property right in the water underlying the land. In application, groundwater authorities could find that current and future regulations restricting a landowner's ability to pump groundwater could require compensation to landowners." Also, it is not clear if the ruling will apply if property is purchased after the creation of a regulating water authority, or how future denials of pumping permits will be affected. Lexology noted "Until the Texas Supreme Court clarifies these issues, litigation will likely ensue and appellate court opinions could begin to splinter, thereby, further muddying groundwater regulations across Texas." There was another case, GG Ranch, LTD, et al, v. the Edwards Aquifer Authority, et al., which had potential for much more far reaching impacts for the Edwards region than the Bragg case. In that case, landowners who never used any Edwards water during the historical time period on which Edwards rights were based filed an application anyway and were denied. They subsequently sued in the Texas Western District Court, alleging their property was taken in violation of the Texas and United States constitutions. If such a suit had been successful, many other landowners might then have filed similar claims. The case was removed to a federal court, which granted a moton by the EAA to dismiss all claims. The court held the GG Ranch plaintiffs failed to state a claim for an equal protection or due process violation, the EAA's permitting scheme and implementation of the scheme is rational, and the plaintiffs were barred from a takings claim by the statute of limitations. The plaintiffs filed an appeal with the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, but missed a deadline to file a brief and the court dismissed the case on August 5, 2015. The Accommodation Doctrine In May of 2016 the Texas Supreme Court issued a ruling that may have implications for some groundwater projects. The Court ruled that Texas' "accommodation doctrine" should also apply to groundwater, in addition to oil and gas. Under this doctrine, owners of underground mineral rights such as oil and gas must accommodate the activities of whoever owns the surface estate. This means, for example, that surface landowners now have a specific legal doctrine on which to challenge plans to pumpwater from below their property. And so some observers hailed the decision as a major victory for landowners. Others were not so positive, because the ruling also establishes the rights of groundwater owners are dominant over those of surface owners. The groundwater owners now have an explicit and expansive right to access the surface tract without the permission of the surface owner and without compensation. Also, the burden of proof under the accommodation doctrine is very high and falls on the surface landowner. In an article published on June 7 in the Texas Tribune, Austin water lawyer Vanessa Puig-Williams noted that landowners must not only prove that drilling operations will substantially impair their existing use of the land and that there are no reasonable alternatives, but they must also prove that reasonable alternatives are available to the producer. Historically, it has been difficult to meet that burden in oil and gas drilling disputes. "The accommodation doctrine is really not that protective of the surface owner's interests," she said. Edwards Water Quality Protecting Edwards water quality is likely to be one of the great natural resource management challenges in Texas in this century. Failure to do so will result in billions of dollars in treatment costs, an environmental service which the Edwards is currently providing for free. Since there is a well-established scientific link between development and runoff water quality, Edwards water quality protection mainly comes down to managing growth and limiting impervious cover. Protecting the Recharge Zone is not enough. It is just as important to protect the quality of water that runs off the Edwards Plateau and ends up as recharge. But with all the layers of jurisdiction and authority shown in the image above, none of which align with the Edwards' hydrogeologic boundaries, it almost goes without saying that managing the Edwards Plateau for water quality will be fragmented and inconsistent. Contributing Zone protections are hugely complicated by the fact that people living on the Edwards Plateau are not Edwards Aquifer users. They do not readily accept the notion of restricting their area's development and implementing rules for the sake of some other people's water supply, especially since they perceive that Edwards users have not been especially proactive in managing development over their own Recharge Zone. In addition, there is growing evidence that protecting the Contributing Zone is also important because of the hydraulic connections between the Edwards and the Trinity. They are more significant than previously believed, but this is not reflected in current TCEQ rules. At present, there is simply no institutional or regulatory framework that can effectively protect Edwards water quality. Most of the Edwards Plateau is not within the jurisdictional boundaries of the Edwards Aquifer Authority, and an expansion seems unlikely. Although the enabling legislation of the EAA seems to authorize that agency to implement water quality rules, the legislation's author has said it does not. The issue was hotly debated in the 2003 and 2007 legislative sessions and no resolution was reached. It was not addressed in the 2009, 2011, 2013, or 2015 sessions. The EAA has several times delayed development of water quality rules because it was concerned such action would result in a private property rights backlash and legislative retaliation. Many contend the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality is the proper agency to regulate for water quality, but so far that agency has not been especially proactive in developing water quality controls, and like the EAA, the TCEQ's authority to apply rules to the Edwards does not extend to most of the Contributing Zone. Meanwhile, there are also significant cultural obstacles to effective water quality management. Texas is a state that is very respectful of private property rights, and many will simply not accept the notion that land use and development should be regulated. On the other hand, a growing number of people don't believe anyone has a private property right to ruin common resources like air and water. However, powerful development interests usually get their way, and so far no lawmakers have been willing or able to take a big-picture view and develop a comprehensive water quality management approach for the Edwards. Texas must eventually find a balance between private property rights and protection of common natural resources. Most environmentalists feel that all the existing rules are a sad joke that are more about avoiding lawsuits than Aquifer protection. This assertion is not a criticism of the staffs of the TCEQ and the EAA - they are all good people who do the best job they can within the legal and regulatory framework they work under. The problem is the framework does not allow them to do very much. For example, the image below shows how all the requirements were met to build a high-density residential subdivision around a collection of cave openings. This is a site that probably should not have been developed at all, but in Texas, failure to give landowners and developers free reign is the same as asking for a lawsuit. In short, environmentalists believe that all the rules are essentially toothless and inadequate.

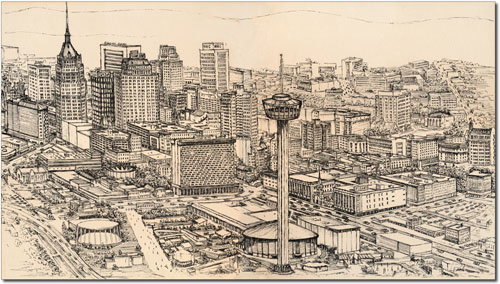

A Water Quality History The issue of Edwards water quality protection deserves a brief historical discussion of how the complex forces of exclusion and expansion were arrayed in some early head-on conflicts between development and water quality. Examining the specific events of those early conflicts, along with one that is more recent, serves to illuminate the underlying forces. This will illustrate how we got where we are today, and what the impediments are to effective water quality protection. Let us begin in the early 1970s. At that time, water quality had barely been brought into focus as either a national or a local public concern. Only a few years earlier, Texas had been forced to establish a water-policy framework to comply with new federal law, the 1965 National Water Quality Act. It had created the Texas Water Quality Board and given it the authority to oversee all efforts to preserve groundwater quality. In San Antonio, a “Task Force Committee for Protection of the Edwards Aquifer” had been created with representatives from local government agencies, but it focused mainly on garbage dumping and sewage disposal, not long-term planning for water quality. The first regulations for protection of the Edwards were issued by the Texas Water Quality Board in 1970. They applied to the recharge and buffer zones in Kinney, Uvalde, Medina, Bexar, Comal, and Hays counties. The rules imposed regulations on underground storage tanks, above-ground storage tanks, and sewer lines. These rules were more or less a cursory nod to new federal requirements, and there was no real commitment on the part of the Water Quality Board to implement truly protective standards. In May of the previous year, Water Quality Board director Hugh Yantis had rankled pollution watchdogs when he signaled his position on Edwards water quality at a Board hearing on the topic. He said San Antonio might have to put up with a "little pollution" and explained that if it was cheaper to clean dirty water than to prevent pollution in the first place, that might be the proper course. The "heart of providing pure water," he said, is to "do it as cheaply as you can." (1) The issue was about to be brought to the fore because San Antonio was poised for explosive growth. San Antonio had once been the largest city in Texas, yet it had long been content to still wear the trappings of a quaint little post-frontier town. Dramatic expansion had been left to Houston and Dallas, and San Antonio was the most exclusive and cultured city in Texas. The tallest office building in town had been built in the 1920s. We all still called it a town, and when you mentioned San Antonio in other states, you had to include “Texas”, otherwise people wouldn’t know where it was. But national economic shifts had stimulated great new interest in warmer southern climates, and local merchants had become restless with the slow pace of growth. San Antonio changed its mind about development.

At that time, many of San Antonio’s wealthier citizens lived in exclusive townships just north of downtown, such as Alamo Heights, Olmos Park, and Terrell Hills, and these places afforded little space for new neighbors. South and west of town, the grassy coastal plain is flat, hot, and undistinguished, with numerous air bases and low-flying aircraft, and it was not seen as a particularly desirable area to live. But to the north lay San Antonio’s jewel, where the land rises up into the picturesque, rocky, and tree-studded Texas Hill Country. As it happens, this is also the Edwards Aquifer Recharge Zone. Growth was poised to leapfrog over the near downtown enclaves and explode over the city’s water supply. Local politics had long been dominated by the Good Government League, which was basically an extension of downtown business capitalists that were focused on finance, retail, and tourism. In the growth areas to the north, suburban expansionists were focused on real estate, retail, and construction. They wanted ever more infrastructure, houses, and malls, and they favored almost any type of economic expansion. The Good Government League was not committed to just any type of growth - it was wary of heavy industrialization and wanted to achieve orderly, rational growth that was focused on services and tourism. While the two factions were not of a single mind regarding the role of government in planning and land use development, they found common ground in a drive to build up the northside service sector in health and education with the South Texas Medical Center and the University of Texas, both on or near the Recharge Zone. Meanwhile, both the staff and the board of the Edwards Underground Water District saw the agency as a support mechanism for economic growth. Since its creation in 1959, it had developed close ties with water development agencies like the Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation. A series of surface water projects was envisioned that would link the Aquifer with various rivers and lakes to create an integrated regional supply system. The focus was on construction and imports, not conservation or protection. This approach was supported by agribusiness and suburban property capitalists, who saw reducing dependence on the Edwards by developing surface water as a way to open up Hill Country land to free enterprise. With large surface water supplies, construction could proceed with less concern for groundwater pollution, the costs passed on to taxpayers in the form of bonded debt. The suburban capitalists were not wholly indifferent to water quality, they simply saw these investments as a reasonable cost for the public to pay to ensure plentiful water while maximizing developer’s access to the most desirable properties. At a hearing before the Texas Water Quality Board on revising their 1970 standards, San Antonio developer Sam Barnes argued that since the city was pursuing ways to acquire surface water, pollution of the Edwards Aquifer “would not be so terrible.” (2) Local conservationists came to have serious doubts about such judgments. The opposition to Aquifer development was led by Fay Sinkin, a forceful and articulate advocate of environmental protection whose main constituency was middle class homeowners who lived on or near the Aquifer. She founded the Aquifer Protection Association, and her movement drew strength and legitimacy from the pro-planning forces in the Good Government League, and also from poor and working class Hispanics who viewed the exclusion of Aquifer lands from development as a means to funnel capital investment back into their own blight-stricken and long neglected neighborhoods. For the northside homeowners, exploding growth in the form of shopping malls, subdivisions, roads, and parking lots was seen as an imminent danger to public health. For the prudent GGL planners, asking taxpayers to bankroll massive reservoir construction was a demand that citizens yield a decided cost advantage to subsidize unregulated expansion. Surface water would be almost 15 times more expensive than Edwards water, and virtually no consideration had been given to conserving or reusing Edwards supplies. Into this environment came Ranch Town. A 1971 edition of Business Week described it: “a group of influential Texans…decided to develop a 9,000-acre tract of richly wooded and hilly land 16 miles northwest of San Antonio into a new town using federal loan guarantees to finance it.” The project was massive, with potential to house 88,000 people, mostly over the Recharge Zone. Like nothing else before it, the Ranch Town proposal turned citizen’s attention to the growth question. Within months, “Aquifer” became a household word. Both conservationists and leading San Antonians opposed it. Downtown business interests affiliated with the Good Government League were concerned that massive federal support for a suburban project would jeopardize their chances for similar grants they were hoping to get for a large redevelopment project in the downtown area. Environmentalists and city planners drew attention to a U. S. Geological Survey report which concluded “…if development on the Recharge Zone of the Aquifer continues at an accelerated rate and if stringent precautions are not taken to prevent the increased waste load from the reaching the Aquifer, deterioration of the chemical and bacteriological quality can be expected.” (3) When a draft environmental impact statement prepared by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) barely mentioned possible threats to the Aquifer, the local environmentalists filed suit and sought a federal injunction against construction on the grounds that HUD had deliberately overlooked the Aquifer in approving the project. To represent them, they hired a young attorney named Phil Hardberger (who decades later served as San Antonio's Mayor). In March of 1972, Hugh Yantis and the Texas Water Quality Board intervened in the suit on behalf of Ranch Town, declaring “there will be no pollution or contamination of the underground water in the area if the developers of the new town continue to comply with Texas law.” (4) Yantis chaired a panel that reviewed a re-worked environmental impact statement and blessed the report with state approval. When Ranch Town went to trial in 1973, trial judge Adrian Spears expressed many environmental concerns, saying that instead of a new town on top of the Aquifer, the area “should be fenced off, trees planted and parks created” on it. (5) In the end, Spears ruled in Ranch Town’s favor, concluding that all applicable federal laws had been followed So it wasn't court action that killed the Ranch, it was the economic downturn of the mid 1970s. In 1979 the S. A. Ranch Partnership announced plans to build 102 homes, a far cry from the tens of thousands initially planned (6). Most of the site became Government Canyon State Natural Area, which was purchased by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department in 1993 in cooperation with the Edwards Aquifer Authority, the San Antonio Water System, the Trust for Public Land, and the federal government Land and Water Conservation Fund.

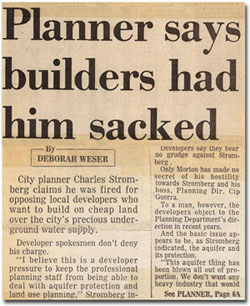

Although Ranch Town won the court battle, public consciousness of water quality issues had been ignited. In 1973 Mrs. Lila Cockrell ran for city council Place 1 calling for an “immediate review of all aspects of development over the Edwards Aquifer.” She said “the city must exercise its full share of responsibility for safeguarding our water supply” and suggested strict controls on population density and city purchase of large acreages in the “critical recharge zone.” (7) Even before Ranch Town went to trial, the Alamo Area Council of Governments had begun trying to forge a region-wide policy on water quality protection. This effort was led by AACOG executive director Al Notzen, whose goal was to win a stronger protection order from the Texas Water Quality Board. Many local officials agreed on a need for stronger action, but at hearings before they Water Quality Board they disagreed on specifics, and this was interpreted by Yantis and the Water Quality Board as a lack of consensus (Plotkin, 1987). Policy making was stymied, so Notzen took another tack, convening a task force of elected representatives from local governments to produce a unified report that called for one and two acre lot sizes for houses using septic tanks and private wells, and city licensed water and sewer systems in new high density subdivisions. It also encouraged the EUWD to assume responsibility for regional pollution controls, but that agency didn’t want the job. Although EUWD had joined the plaintiffs in the Ranch Town suit, it also publicly protested any police role, insisting this function should be left to the individual counties (8). Protection orders that came out of the Water Quality Board’s office included some of the AACOG proposals but lacked means of enforcement and were widely criticized as woefully inadequate. The Ranch Town debate also resulted in a permanent split between the business interest factions that had previously been able to cooperate on at least some development issues. Many members of the Good Government League had become concerned with the potential water quality consequences of unchecked expansion and had begun to favor more careful approaches to growth. Support grew within the City Water Board and other city agencies for a more controlled advance. City planners began speaking of the high cost of providing city services when "leapfrog" development demanded new infrastructure in far-flung areas. It would be far more economical for taxpayers, they argued, if development focused on vacant lands closer to town. Suburban capitalists were not happy with the GGL's planning approach. In 1973, multi-millionaire Charles Becker, who had inherited a supermarket chain from his father, led San Antonio’s urban land merchants in a successful revolt against the GGL. He won the Mayor’s office that year and quickly took control of key city agencies such as the City Water Board, replacing their directors with northside builders who had been complaining that CWB policies were stunting San Antonio’s growth (9). Local conservationists remained focused on the water quality issue and continued to pressure the Water Quality Board for more protections. Water Pollution Abatement Plans (WPAPs) were first required in 1974, but enforcement and oversight were non-existent, as the EUWD continued to resist taking on any responsibility for water quality. AACOG and others continued to criticize the Water Quality Board’s standards – Notzen declared the Board’s standards would “have the result of placing the burden for cost for keeping the recharge clean on the taxpayers county-wide rather than on the developers who are building on the Recharge Zone” (10). By 1975, construction interests were intent on permanently dismantling the Good Government League. They formed the Independent Team to pursue replacement of the GGL as the ruling party in the city. Mrs. Lila Cockrell, the last of the GGL candidates, won the mayor’s office but the new party won a majority of council seats and quickly began exercising control. It dismissed the city’s planning director and appointed the president of the Greater San Antonio Chamber of Commerce to the chair of the Planning Commission. The city’s previous planning director, Charles Stromberg, claimed he was fired at the behest of builders, and the builders didn't deny it. He had made the fatal mistake of preparing an "Alternative Growth Study", which suggested that San Antonio’s growth could be kept inside Loop 410. At public meetings, Stromberg and his staff had pointed out how the high cost of expansion into vacant areas was subsidized by the rest of the tax base, to the benefit of a few developers and land owners. With Stromberg's firing, City Hall was clearly under the control of developers. They moved quickly to squelch any more talk among city planners of development that focused on areas closer to town. In 1975, attention turned to a federal question – whether the Edwards should be designated a “Sole Source” aquifer under provisions of the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act (11). The designation would prohibit federal funds for any project that might contribute to pollution of the Aquifer, and would require EPA review of any project that received federal funds. Hearings drew large turnouts at which most speakers were opposed (12), (13), and the developer-controlled City Water Board passed a resolution against it (14). Despite objections, the Edwards Aquifer was the first to be designated as a Sole Source Aquifer.

Although the citizen's referendum didn't stick, the public was solidly on record as supporting Aquifer protection, and conservationists continued to pursue additional controls. In 1977, modest rules changes were adopted by the state in requirements that new underground storage tank sites had to be approved prior to construction, and sites were required to have double-walled tanks and piping as well as a method of leak detection. Though modest gains were made, no progress was made on the most significant threats - population density and impervious cover. It was becoming clear that given San Antonio's limited powers of self-protection, the Aquifer's multijurisdictional reach, the conservative bias of the governmental framework, and the power of business interests at all levels of the political system, there might be little that concerned citizens could do to protect the Edwards. The situation is remarkably similar today. Two years after the takeover of city government by Becker's Independent Team, water quality got back on the council agenda when the makeup of city council was profoundly changed by forced compliance with the Voting Rights Act. Elections had always been held at-large, which guaranteed control by wealthy upper-class businessmen, and also guaranteed dilution of Hispanic and African-American voting power. Review of the voting system by the Justice Department resulted in a new electoral framework with ten geographic council districts, including six from the south, west, and east sides. The first election under the new system was held in April of 1977, forever ending domination by either the Good Government League or the Independent Team. With a new representative council in place, the tenor of the discussion shifted from not whether development controls ought to be in place, but what kind of controls. The city contracted with the Metcalf & Eddy consulting firm to weigh the risks of pollution from Recharge Zone development and recommend a course of action. Fay Sinkin and the Aquifer Protection Association, backed by a new Hispanic activist association, Citizens Organized for Public Service (COPS) began aggressively pursuing an 18 month total ban on building over the Recharge Zone, until the study could be completed. The historic moratorium was passed on June 10, 1977, before a screaming, applauding crowd of several hundred Aquifer proponents. Reaction from suburban capitalists was swift and angry. Within days, one developer filed a $750 million class action suit in federal court, charging an unconstitutional taking of private property. In state court, a group of eight developers brought another suit for $750 million against six council members who had voted for the moratorium. Within weeks, both state and federal courts issued temporary injunctions against implementation of the building ban. In early 1979, Metcalf & Eddy delivered their long-awaited study of possible Edwards protection methods. It concluded "The municipalities and counties may be helpless in protecting the health, welfare and safety of their citizens." Because of the vast size and multijurisdictional reach of the Recharge Zone, the consultants concluded that effective protections could only be carried out at the state level, but saw little hope that would occur. It recommended techniques such as lining streambeds that cross the Recharge Zone with concrete, and piping drinking water into the region when Edwards water becomes too polluted to drink. Aquifer advocates were not satisfied with those solutions.

The Metcalf & Eddy study also suggested that up to 85% of the Recharge Zone within the city limits could be developed if careful protection measures were in place, but the consultants clearly indicated that controls on development were preferable. Today we know water quality deteriorates when developments exceeds 10-15% of a property. In response to Metcalf & Eddy's suggestion for controls, attorneys quickly issued warnings to local officials that lawsuits would result if the "civil rights" of North Side property owners were violated. One line of reasoning was that since the water San Antonio uses comes from west of town, the city could not legitimately use its police powers to regulate development over the Recharge Zone because "it isn't protecting San Antonio water anyway."