|

|

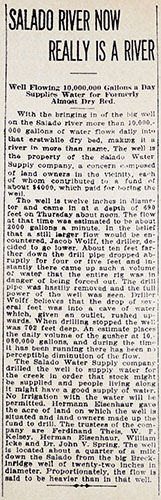

Salado Creek and the Farmer's Well In 1912, Ferdinand Theis went around to his neighbors and collected $100 from each for the purpose of drilling a well (Theis, 1987). On October 12 of 1912, the San Antonio Light reported:

In 1914 the farmers purchased the one-acre tract from Eisenhauer for $200. Another nearby tract of 0.46 acres was purchased for a second well, but it was never drilled. The farmers also built a dam across Salado Creek just above its confluence with the San Antonio River, forming a three mile lake, but it washed out during floods. The U.S. Government eventually purchased all the land around the farmers' tracts, making the well a private oasis in the center of Fort Sam Houston. During dry times, several Ft. Sam commanders ordered the well capped until it was explained to them that the well was privately owned and not a part of the military base.

By 1962, internal troubles had developed within the farmer' association. The original plan allowed garden plowing irrigation only, but many began using the water for all types of irrigation, leaving little for others farther downstream. By 1975, with the continued drilling of numerous Edwards wells and rapid urban development, artesian flows slowed considerably and the Creek water became unsafe to drink. With the extension of municipal water services to the area, most were able to abandon their reliance on flows from the well.

In 1991, two events brought public focus onto the well. The Sierra Club had filed suit to protect the endangered species in Comal and San Marcos Springs, and Ronnie Pucek had drilled his massive artesian well at the Catfish Farm. By August of that year, a string of Letters to the Editor complained about the well's uncontrolled flow at a time when landscape watering had been restricted to help maintain springflow for endangered species. Letters also compared the Farmer's Well to the Catfish Farm well, which was under tremendous public scrutiny. So the Farmer's Well as deemed a "waste" and was plugged by the Edwards Underground Water District in September of 1991.

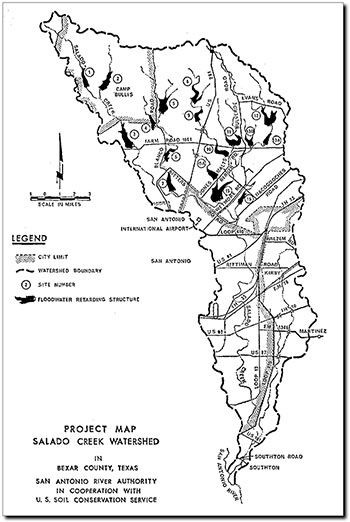

Salado Creek Watershed Flood Control In the 1960s, the San Antonio River Authority, the U.S. Soil Conservation Service, and the Army Corps of Engineers developed a plan for a series of dams in the Salado Creek watershed that would offer both flood control and the opportunity to develop parks and open spaces. One of these sites became the Northeast Preserves, one of San Antonio's favorite playgrounds. Some of the dams were built on or above the Recharge Zone, so they also had the side effect of increasing Edwards Aquifer recharge. In fact, most of them would probably not have been built had it not been for the Aquifer recharge benefits. By the 1960s, land in the area was already considered very expensive. Similar flood control dams had already been built on Martinez and Calaveras Creeks, and leading local rancher and conservationist Erwin E. Voigt had been instrumental in obtaining easements and funding. He was asked by the San Antonio River Authority to help them in obtaining easements for the Salado Creek project. After he arranged to obtain $57,000 for surveys by the State Board of Engineers, the agency turned down the project, because they said the costs would exceed the benefits. Voigt called two members of the State Board with whom he was acquainted and asked them about the rejection, saying "Did you give us credit for the value of this project to the underground recharging system?" They replied "No, we have never done that before." Voigt replied "Well, it's high time you did!" The next day they called Voigt, came down to the River Authority offices, gave the project credit for recharge benefits, and approved it (Jarrett, 1973). Work got underway in the spring of 1970, with the first dam built on Camp Bullis at a cost of $177,000. Over the next several decades, flood control work and urban encroachment radically changed Salado Creek from a scenic riparian corridor into a forgotten disposal channel. Except that some never forgot. Residents often talked about a trail system along Salado Creek to link north Bexar county to the southern part of the county and the San Antonio missions. They felt that hiking and biking trails, parks, shallow pools, and waterfalls would help lead to an understanding of nature in urban environments and offer linkages to develop a greater sense of community among people living near the creek. In 1988, the Salado Creek Foundation was formed to work toward these goals. When the Farmer's Well was plugged in 1992, the group found new vigor to work with community leaders and city utilities to begin planning for restorations and re-establishment of the baseflow that disappeared with the well plugging. In addition to its value as a natural community resource, there is a profound list of prehistoric and historic uses and events surrounding Salado Creek that deserve to be remembered and highlighted. The corridor was a major prehistoric transportation route for native tribes, and signal historic events such as the Battle of Rosillo (1842) occurred on its banks. Restoration of Flow and Creating Community Linkages In 1995, the first of several plans was developed to return Salado Creek to something that more closely resembles its natural state while enhancing both recreation and flood control. In December '95, a plan developed by the engineering firm of Groves and Associates for an ad hoc committee in City Council District 2 was unveiled for the seven mile stretch of Salado Creek through that district. It called for a series of shallow pools and 35 small cascading waterfalls; and it focused mainly on the stream channel itself and physical connections along the creek like greenbelts and bike paths. A key aspect of the Groves plan was extending the SAWS recycled water line north to Eisenhauer Road so flow would pass through the neighborhoods of Wilshire Park and Wilshire Terrace. In February '96, an Environmental Design charette held by the American Institute of Architects produced another plan that complemented the Groves plan in some ways and conflicted in others. The charette plan dealt with a wider target area and included development up and away from the creek and broader aspects such as housing. One big difference was the charette plan called for transportation access in certain places while the Groves study found neighborhood associations did not want any roads along the trail system. In March '96, City Councilwoman Ruth Jones McClendon asked Council to make the ad hoc committee into a full commission so the Salado Creek trail idea could be extended beyond District 2 and so the City could apply for federal and state grants. Also in 1996, the San Antonio Water System sought public input on its plans to construct a massive recycled water distribution system to supply non-potable water for uses like golf course irrigation and industrial processes. Supporters of Salado Creek approached SAWS and asked if a discharge location could be included on Salado Creek so there could once more be a reliable source of water. For distribution systems like the one SAWS planned, it is operationally beneficial to have locations where releases can be made when demand for water is low, thereby maintaining flow and water quality within the pipeline. As a public agency, SAWS also wanted to support community goals, and so a discharge at Rittiman Road was included in plans for the $140 million project. In April '97 city staff completed a study of the Salado watershed that identified 169 residences, 65 businesses, and 10 apartments that would be subject to flooding during a 100 year flood. They recommended more than $25 million in improvements, most for building bridges and culverts. Recommendations also included a levee that would remove 99 homes from the floodplain, channelizing parts of the river, rerouting some roads, and purchasing 12 houses and five other buildings. In December '97 the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission announced Salado Creek would be among the first waterways to be included in an initiative to determine the amount of pollutants the waterway can receive and still meet state standards. The initiative was in response to a mandate by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that states begin enforcing portions of the federal Clean Water Act that deals with surface water quality. Salado Creek was listed on the Environmental Protection Agency's 303(d) list of Threatened and Impaired Waterbodies. Problems found in Salado Creek included low levels of dissolved oxygen, elevated levels of diazinon, and elevated levels of fecal coliform bacteria. The state study determined TMDL limits, the "total maximum daily load", so that methods to meet those limits could be implemented. In October '98, record floods left a band of destruction and debris in Salado Creek, stripping some sections of vegetative cover and leaving them vulnerable to erosion. Since waterway greenbelts can provide recreational opportunities in dry times and are a hedge against flood damage during heavy rains, city leaders began working toward a bond issue to preserve both Salado Creek and Leon Creek for flood control and city parks. In February 2000 San Antonio was awarded a $2 million state grant to turn three miles of Salado Creek banks into hike and bike trails. The project involved linking the city's Willow Springs golf course with MLK Park, DaFoste Park, J Street Park, and the county's Comanche Park. Residents were excited about the prospect of using the trail for jogging and bike riding. Work also included a 10 foot wide concrete trail, landscaping, and trail markers. The city also began installing trails wherever it could as part of regularly scheduled drainage work along Salado Creek. Just before his death in April 2000, renowned art collector Robert Tobin arranged for donation of his 60 acres along Salado Creek to the City to help realize the dream of a a linear park. Tobin was an important benefactor of many nationally renowned cultural institutions and was a very environmentally conscious person before environmental sensitivity was an issue. The land between Austin Hwy and Loop 410 and east of Ira Lee Drive will be known as Robert L. B. Tobin Park. On May 6 2000, voters approved Proposition 3, a 1/8 cent sales tax, to raise $20 million to buy land along Leon and Salado Creeks to be used as natural floodways, open space, and hike & bike trails. Nearly 20 miles of the creek was targeted for improvements aimed at transforming the waterway into a linear park, binding together many city parks, and providing flood control. In March 2001, SAWS completed the first phase of its recycled water distribution system, which included the Rittiman Road discharge, and Salado Creek began to flow again. The discharge location is just a short distance upstream from where the Farmer's Well used to flow. The first discharge occurred on March 6, and the reliable flow of water began making visible improvements in Salado Creek very quickly. Subsequently, the Creek was removed from the EPA list of Impaired Waterbodies for dissolved oxygen. In May of 2005, voters reauthorized Proposition 3 to raise another $45 million for linear parks along creeks. In July of 2008, the city unveiled plans to complete 17 miles of trails on Leon and Salado Creek by the summer of 2009. By November of 2008, the first stretch had opened - a 1.7 mile segment between Huebner and Blanco roads. Nearby resident Dana Lesueur said "We are so excited. Oh my gosh, we have wanted this forever. It's just gorgeous. You can come here any time and see walkers and ladies pushing strollers." By 2009, plans for additional trails were rolling along, although officials said some sections would have to wait until completion of the Wurzbach Parkway. In 2010, a 2.3 mile stretch opened connecting Pecan Valley Lake to the Comanche and Covington parks at Rigsby Avenue. By the fall of 2013, more than 18 miles of trails had been completed, and three more miles were completed in 2014 and 2015.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Materials used to prepare this section: "Two Private Oases in Center of Ft. Sam" San Antonio Light, April 22, 1962. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||