|

|

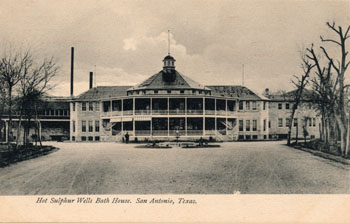

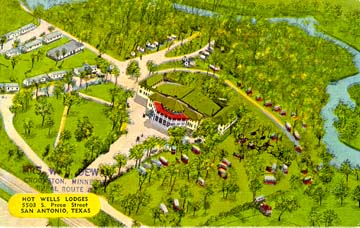

The Hot Wells Hotel and Spa In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Hot Wells site on the San Antonio River was home to several versions of a health spa and resort that piped sulfurous water from a hot Edwards well to health-inducing swimming pools and baths. Much of the site's history has been defined by fire. The first structure burned to the ground in 1894 after only one year of operation. The most famous version of the spa was its replacement, a lavish Victorian style structure built in 1900 that became a renowned, world-class vacation destination for celebrities, world leaders, and wealthy industrialists. Some of its visitors were Will Rogers, Charlie Chaplin, Teddy Roosevelt, Porfirio Diaz, Tom Mix, Douglas Fairbanks, and Cecil B. De Mille (Fox and Highley, 1985). The legendary hotel burned in 1925, and the bath house burned twice, in 1988 and 1997. But the remains of the bath house are still standing for decades there were hopes the site could be revitalized. In 2018, they are becoming the center-piece of a new county park.

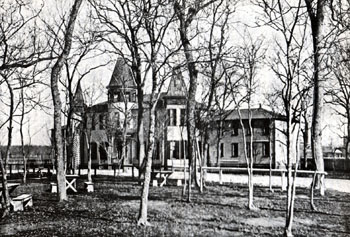

A Brief History In 1892 the Southwestern Lunatic Asylum (later known as the San Antonio State Hospital) drilled a well to supply water to their new facility on South Presa Street near the San Antonio River. At that time, only a few Edwards wells had been drilled, and no one understood the site was near the saline/fresh water interface of the Edwards Aquifer, where hot, sulfurous wells are common. Instead of sweet potable Edwards water, the well instead produced 104 degree water with a strong sulfur odor that was unfit for domestic use at the Asylum. The volume was copious - about 180,000 gallons per day, and since many people believed in the healing powers of hot waters, the medicinal and recreational potential of the strong-flowing well was recognized immediately. To defray the expense of arranging for an alternate water supply, the Asylum leased the well waters to Charles Scheuermeyer for $75, who established a resort nearby and advertised the medicinal benefits of its waters. According to Scheuermeyer, who had the water analyzed by the State University in Austin, the waters would cure just about anything, including rheumatism, skin diseases, and blood poisoning. Shacklett's Natural Hot Sulphur Wells In 1893 the Asylum's annual report noted that a special act of the Legislature enabled them to lease the sulphur water for 10 years, and McClellan Shacklett bid $500 per year, winning out over Scheuermeyer. The lease required erection of a first-class bathhouse to cost at least $4,500 and a large sanitarium at a cost of at least $12,000. Shacklett used the resort at Hot Springs, Arkansas as a model and drew up plans for a natatorium with private baths and pools, billiard and drawing rooms, and accommodations for 200 guests. He purchased a 10-acre pecan grove bordered by a graceful v-shaped bend in the San Antonio River, and he transformed it into a landscaped park with an elegant carriage drive leading to the main building. By the summer of 1894, Shacklett's Natural Hot Sulphur Wells drew large crowds, electric streetcars ran to the site every 20 minutes, and festive social events were celebrated in local newspaper accounts. An advertisement in the San Antonio Daily Express declared the waters were:

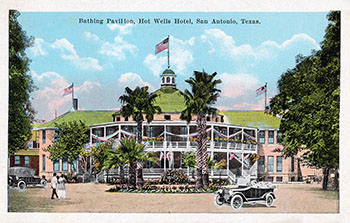

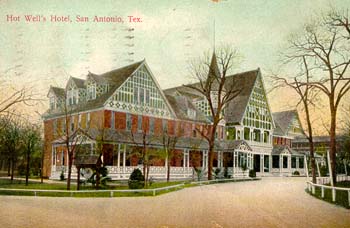

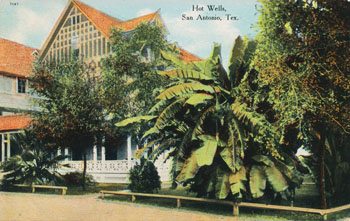

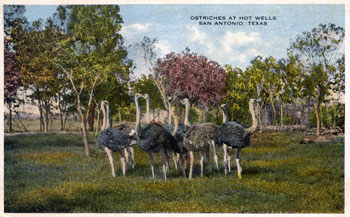

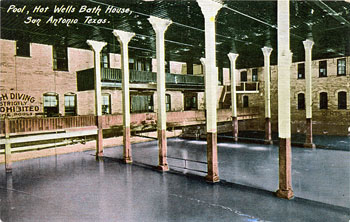

Shacklett also assembled a menagerie of exotic animals, including Mexican lions and a bear shipped to him by Judge Roy Bean. The San Antonio Daily Express reported that Judge Bean had spent an afternoon with Shacklett in San Antonio and had bragged about killing seven bears in one afternoon near Langry. Shacklett refused to believe him, so Bean shipped him an alleged wild bear and a letter describing the harrowing capture of the ferocious and dangerous animal. The following day, an anonymous traveling salesman wrote the newspaper and said the bear was not wild at all but was a beer-drinking pet that Bean had kept in his saloon. On December 23, 1894, the bathhouse was completely destroyed by a fire that raged through the building in less than an hour. Shacklett braved fire and smoke to rescue guests and no injuries were reported, but the $17,000 structure was lost. Shacklett vowed to rebuild a bigger and better facility and by March had opened a temporary facility, but plans to rebuild on a larger scale apparently never materialized. The Golden Era In November 1899, a group of local and Northern investors secured a 25-year lease on the Asylum's waters and announced plans to build a "large and commodious hotel with attractive grounds and park in addition to the bath house and all other conveniences and ample capitol with which to make improvements of the highest class in accordance with modern demands and of a permanent nature." The investors formed the Texas Hot Sulphur Water Sanitarium Company, purchased Shacklett's property and an additional tract, and by late 1900 had completed a bath house and three swimming pools. The bath house had three public 64x90' pools and 45 private rooms with marble partitions and solid porcelain tubs, separate facilities for ladies and gentlemen, and steam, Turkish, Roman, needle, and shower baths. By 1902 a hotel was completed with 80 rooms and modern-day conveniences such as hot and cold water, steam heat, electric and gas lights, and individual telephones. An ostrich farm was relocated from San Pedro Springs so that local ladies could easily acquire feathers, an important component of ladies fashion of the day. At some point, a well was drilled on the property and water was no longer piped from the Asylum.

In 1908 an expansion to the hotel was completed, making it one of the largest in the southwest, and advertisements appeared in Chicago and New York newspapers. The local papers frequently mentioned the resort's hosting of social events like domino parties, concerts, lectures, and dances. Gambling appears to have been a major activity, with bets placed on ostrich and horse races. On the pastoral grounds that gently sloped down to the San Antonio River, there was tennis, croquet, and horseback riding. On the River there was boating and swimming, and a swinging bridge provided free access to the ruins of the San Jose Mission.

In 1909, Southern Pacific railroad tycoon E. H. Harriman made an extended visit to the Hot Wells resort to recover from ill health, and he built a side track to the site to accommodate his private railroad cars. He did not recover and passed away in September of that year, but the rail spur enabled rich and famous visitors from all over the country to be delivered to the resort's doorstep. Some, such as Sarah Bernhardt, brought their own private railroad cars. In 1910 and 1911 the property was home to the Star Film Company, a movie studio that made 71 films in San Antonio including the first about the battle of the Alamo. Several other film companies filmed early silent westerns in the area and used the hotel and bath house for their studios. During this time, the resort was in what may retrospectivally be called its "heyday."

By 1915, World War I had a serious impact on business at the resort, as national resources and attention were diverted from leisure pursuits. In 1920, Prohibition cut off a major source of profits for hospitality-based businesses that had previously served alcoholic beverages. As the resort's popularity declined, management began serving formal dinners and hosting concerts by popular orchestras to draw crowds from San Antonio, but this strategy only worked for a while. In 1923, the property was sold to a Christian Science congregation for conversion to a parochial institute called the El Dorado School. The hotel served as a dormitory until it was destroyed by fire on January 17, 1925. Firefighters saved the bath house by concentrating their efforts on the passageway from the bath house to the hotel.

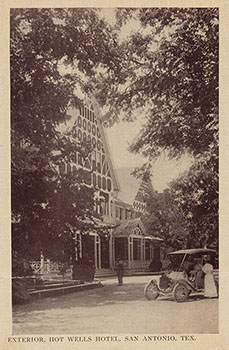

The postcard on the left was mailed in 1907. In the year 2000 photo at right, some of the windows on the left side are still recognizable and the palm trees have survived and grown much larger. Like ghostly reminders of past glory, the roadster, the wagon, and the ladies have been digitally placed in the year 2000 photo about where they were in 1907. The back of the postcard says:

The Tourist Cottage Era In 1927 Charles Dubose, John C. Kirkwood, and M. H. Braden formed the Hot Wells Tourist Park Company and constructed tourist cottages around the foundation of the old hotel and elsewhere around the grounds, and guests were allowed to use the swimming pool. In 1942 the property was purchased by Mrs. Cleo S. Jones, and she and her husband Ralph converted it into a motel and trailer park. The lobby of the bath house was reopened as a bar and grill called The Flame Room, offering burgers, beer, and swimming in the hot sulfur pools.

In 1974, the porcelain bathtubs were still in place in the abandoned private bathrooms, and a charred section of the old hotel was still visible. Mr. Jones operated The Flame Room until 1977, and the contents of the old bathhouse were auctioned off in August of that year. Mr. Jones expressed a willingness to sell the property to anyone who would refurbish and restore it, and Mayor Lila Cockrell supported including it in plans to revitalize and improve the Mission Parkway corridor that runs from downtown to Mission Espada, past all five San Antonio missions. Since the site closed in 1977, many potential investors have contemplated restoring the hotel, but little refurbishing has been accomplished. In 1979 Kathryn Scheer bought the property with visions of turning it into a holistic health care center. She spent 15 years looking for investors with no success. In 1988 lightning struck the spa's tower, causing a fire that gutted the building. Scheer lost the property to the county in 1994 because of unpaid back taxes. In 1990 archaeologists noted the remains of a previously unrecognized swimming pool near the railroad tracks, just east of the old hotel site. The outline of what appeared to be a brick foundation wall had been documented in 1984, and archaeologists conjectured it may have been a railroad station. When trenching related to a 1990 wastewater improvements project intersected the structure, archaeologists were on hand to glean more information. They noted the brick patterning was exactly the same as the Hot Wells bath house, the floor of the structure sloped, and there was a visible water line. Buttressing and increased wall thickness at the deep end to contain water pressure was considered to be further evidence that it was indeed a bathing pool (Fox and Cox, 1990). On October 20, 1997 a fire caused by arson destroyed the midsection of the bath house and made it seem more unlikely the hotel could ever be restored. But some residents never lost hope for the area. Mike Lance, President of the San Jose Development Corporation, and other neighborhood activists sought permission from the Commissioner's Court to draw up plans for the area. Their goal was to see some kind of resort hotel built that would serve visitors coming to see the missions.

In March 1999 the site was purchased at auction by Liberty Properties for $161,000. Company president James Lifshutz wants to preserve the bath house and make it available to the public with historical markers and interpretive displays. In 2000 the San Antonio City Council voted to spend $50,000 on a study to determine what type of development would be best for Hot Wells. The hotel is just one component of a larger redevelopment plan for the South Presa street commercial corridor. But on May 6, 2000 voters turned down Proposition 4, which would have authorized a sales tax to raise $30 million over 10 years for a Commercial Corridor Revitalization and Improvement Fund. If approved, $1.5 million had been earmarked for infrastructure and access improvements to assist in redevelopment of the Hot Wells site. In 2003, a series of public meetings was held to get input on the best uses for the property. The meetings were conducted by the Hot Wells Institute, a non-profit, community-based organization established to cultivate a full appreciation of the natural, ecological, and cultural aspects of the Hot Wells site. The Institute was hired by Avenidas, Inc., the economic development agency for the South San Antonio Chamber of Commerce, to lead the community through the strategic planning process. Potential uses included a hotel, a spa, a wellness center, and a resort. It is hoped the report can be used to convince developers and investors of Hot Wells' potential. By 2004, owner James Lifshutz had begun cleaning up the property and shoring up walls. On August 31 of that year, the Hot Well Institute hosted a community-awareness event and about 100 interested citizens took advantage of a rare chance to see the property and get wet in the pool. In April of 2005, modular spaces were set up on the property to establish an art enclave. Some photos of the 2004 Community-Awareness event:

In 2011, fire once again ravaged the resort's remain. At about 7:40 pm on April 27, fire was reported in several of the dilapidated buildings. Fire officials said the blaze had multiple points of origin and was the second fire of the day at the site. The first was determined to be arson, and police searched the surrounding woods for a suspect.

In August of 2012, Bexar county announced it would consider taking a role in resurrecting Hot Wells by transforming three acres of the site into a county park that would connect to the hike and bike trails on the Mission Reach of the San Antonio River. Under a plan presented to county commissioners, owner James Lifshutz would donate the acreage to the county, which in turn would spend about $2.7 million to shore up buildings, build street access and sidewalks, and install lighting, landscaping, and bathrooms. A non-profit conservancy would be established to raise money for paying for long-term care of the park By 2013, plans were advancing - the Hot Wells Conservancy was created to preserve the vestiges of the historic hotel and provide educational, cultural, and environmental programming. On May 15 it established a Facebook presence and had also begun work on designing a website. In August of 2013, news reports indicated the hot artesian well would be plugged. The Edwards Aquifer Authority board voted to pay more than $144,000 for a caisson installation project that would lead to a cap on the well. This is not really surprising - free flowing Edwards wells are not exactly legal anymore, and many unpermitted wells have been plugged or capped since Edwards pumping became limited by law. In January of 2014 the well was indeed plugged, thereby ending an era. Representatives of the Hot Wells Conservancy said they hoped to be able to raise enough money to someday drill a new well and acquire Edwards Aquifer water rights that would be required to produce water from it. This would be an expensive proposition - a new well would likely cost more than $30,000 and to maintain a minimal flow of 15 gallons per minute, about 24 acre-feet per would be required. Edwards rights currently trade at more than $5,000 per acre-foot (but can be leased for perhaps less than $200 per acre-foot). In October of 2015 the dream of revitalizing the site took a major step towards reality when Bexar county approved $4 million in improvements, enabled by a land donation from James Lifshutz of part of his 21 acre tract. The site was to become the county's first cultural park (San Pedro Culture Park beat them to the honor in 2018). Improvements would include lighting, signs, connection to reach Mission Reach trails, utilities, and ruins preservation. County Judge Nelson Wolff thanked James Lifshutz and said "It's been decades. Everybody's talked about trying to do something with Hot Wells, and it looks like we may get there." Lifshutz thanked everyone that has been working on the project and said "The Hot Wells is a significant historic resource that kind of already belongs to the public in their hearts and minds, and I'm just pleased to make it official." In December of 2016 Commissioner's Court authorized spending $5.8 million on the park and selected Davila Construction to lead the project. County Judge Nelson Wolff said "It's one of the more important projects that we're doing. It is indeed a very historic place." In early 2017 the project was stalled by environmental cleanup and access issues. There was a lien on the property from the Edwards Aquifer Authority for $344,000 for the cost of plugging the well in 2014, and there were also unexpected issues with lead contamination of the soils. In addition, the railroad track that used to bring famous visitors to the property now made access difficult because it runs in front of the property along South Presa Street. Getting to the site might involve gaining access through an adjacent property owned by the Torres family, but they have been there since the Civil War and did not want to sell. Precinct 1 Commissioner Sergio "Chico" Rodriguez assured the family he would not take their property against their will by eminent domain, but in a later interview with the Express-News he did not rule it out. "We want to work with them, of course," Rodriguez said. "I'm not saying the county won't use eminent domain, but that's not a scare tactic that I want to say we want to use on the Torres." You the reader can try and figure out what that means. By April of 2017 negotiations over lien costs and lead cleanup had produced a compromise. The county agreed to pay for the lien in proportion to the number of acres it owns and also agreed to pay for the lead cleanup to quality for a $1 million grant from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Dept. to develop the park. By the summer of 2018 work was well underway to stabilize the bath house ruins. The plans for the Hot Wells County Park included community garden programs, weddings, art exhibitions, and other events such as screenings of silent movies in tribute to the site's historical connection to the early film industry.

On April 30, 2019, the new Park opened to the public. Long-range future plans for the site include restoration of a 3 story section of the bathhouse for a demonstration kitchen, meeting room, student computer room, and a small gift store and museum display. Also in April 2019, James Lifshutz commenced the drilling of a new hot well for a spa complex near the bathhouse that will continue the tradition of "healing sulfur waters". Contrary to numerous news reports that characterized it as a "natural spring", it is not a spring. It is a well. There have never been any natural springs at Hot Wells. In August of 2020, the Historic Design and Review Commission approved plans to build the spa structure, food truck or RV parking, and a connection to the right-of-way at the Mission Reach of the San Antonio River. Future plans may also include a restaurant and bar. Developer James Lifshutz said "There's a lot of romance about the property - its history, its mythology, the place it holds in the hearts of many San Antonians. That's the principle motivation for doing this, is to capture the history and romance and bring it back in a different form."

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Materials used to prepare this section: Anne A. and Cheryl Lynn Highley (1985). History and Archaeology of the Hot Wells Hotel Site, 41 BX237. San Antonio: The University of Texas at San Antonio Archaeological Survey Report No. 152. Fox, Anne and I. Waynne Cox (1990). Archaeological Monitoring in Connection With the San Antonio Wastewater Facilities Improvements Program, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas. San Antonio: The University of Texas at San Antonio Archaeological Survey Report No. 194. "Hope for revival of Hot Wells may be up in smoke" San Antonio Express-News, October, 1 1997. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||