|

|

Cloud Seeding For a while, there was growing hope that weather modification in the form of cloud seeding could provide more water for the Edwards Aquifer and also potentially reduce agricultural demand. In 2003, scientists at the National Academy of Sciences concluded there is no scientific evidence that it works (1). They had reached the same conclusion previously in 1959 (2). In 2010, the American Meteorological Society offered an information statement on planned weather modification through cloud seeding which was obviously written by a committee and did not offer a definitive statement. But in the context of discussing other weather modification techniques, it seemed to suggest that no scientific basis has been demonstrated for cloud seeding, either statistically or physically (see their statement). Although nobody with any real credibility claims that cloud seeding works, that has not stopped many from trying. In central Texas, they have been trying for more than 120 years. During an intense drought in the early 1890s, interest in rainmaking around San Antonio was high. Rainmaking practitioners had developed secret concoctions and were using artillery, ballons, kites, and towers to blast or expel particles and gaseous emissions into the heavens. In 1891, the San Antonio Board of Trade appointed a committee to look into the possibility of bringing a rainmaker to south Texas and to inquire as to how many 8-inch mortar guns were on hand at the Rock Island Arsenal in Illinois (3). In April of 1892, committee chairman W. A. Bowen reported there were six, and several railroads said they would cheerfully render full transportation free of charge. But he also recommended the use of balloons instead of mortars (4). He called on several gentlemen under the charge of noted rainmaker General Robert G. Dyrenforth to meet with the Board and discuss arrangements using that method. On November 14, 1892, the Board was pleased to receive and make welcome Messrs. John H. King and John H. Dickinson, who gave an account of their experiments under General Dyrenforth. They advised the Board it was not necessary to discuss the importance of this work, because if rain can be produced at will, land values will be raised by 300 percent. They told how they had received an appropriation from Congress and had been conducting experiments in South Dakota, but "the government was too slow, and the western people had become interested, so they were here, with their balloons, power, and other apparatus in Galveston ready to be sent, and now they wanted the citizens of San Antonio to come to the front and help by a kind word and a small subscription." The Board passed a resolution heartily recommending their work to the citizens of San Antonio (5). That same day, Mr. King was on hand when City Council convened and was invited to address the body on the subject. He gave a detailed account of their experiments, and Mayor Callaghan arrived as he was finishing. The Mayor seemed "somewhat vexed over the matter, the reason probably being because he was not consulted first of all." Some discussion followed, in which Callaghan said "Our city is not able financially to contribute to any such a thing, and gentlemen of the council, I most seriously object to having anything to do with it." When a resolution on the matter was proposed, Callaghan again protested, but his was the only vote in oppositon when Council resolved "We welcome this experimental expedition to San Antonio and commend the enterprise to our people that they may render such encouragement as the great work in which they are engaged merits." (6) Several weeks later, General Dyrenforth and his party departed San Antonio, having failed to make any rain. But Dyrenforth was satisfied with his experiment from a scientific standpoint (7). An observer from the West End subdivision noted:

The Brownsville Herald offered what they called a Sensible Suggestion:

In 1934, the Associated Press described the effectiveness of some of the early rainmaking methods such as Dyrenforth's:

Cloud seeding as we know it today got its start in 1946 when Dr. Vincent J. Schaefer, working at the General Electric Laboratory in New York, was involved with research to create artificial clouds in a chilled chamber. During one experiment, Schaefer thought the chamber was too warm and placed dry ice inside to cool it. Water vapor in the chamber formed a cloud around the dry ice. The ice crystals in the dry ice had provided a nucleus around which droplets of water could form inside the chamber. Natural rainfall works much the same way. Ice crystals are formed when cold water contacts particles of dust, salt, or sand. The ice crystals provide a nucleus around which water droplets can attach, increasing the size of the droplet. When the droplet becomes large enough, it falls as rain. This is the "cold rain" process, also called the "static method". Cloud seeding is thought to increase the number of these nuclei available to take greater advantage of the moisture in the cloud and form raindrops that otherwise would not have formed. For the "cold rain" process, silver iodide can be used as a nuclei because its structure is very similar to ice crystals.

Another process, the "warm rain" process, usually involves clouds in tropical regions that never reach the freezing point. In these clouds, raindrops form around a "hygroscopic nuclei", a particle that attracts water such as salt or dust. Small droplets collide and coalesce until they form a drop large enough to fall. To encourage the "warm rain" process, calcium chloride is usually used to provide the nucleus for raindrop formation. After Dr. Schaefer discovered the principle of modern-day cloud seeding, interest in south Texas was revived. By 1950, the Guadalupe-Medina Floodwater Reclamation Association was promoting a cloud seeding program for the Medina River watershed. It set about raising $30,000 for the effort and began negotiations with a firm from Phoenix that could either install silver iodide generators on the ground or deliver the particles by airplane (11). Rainmakers continued to develop secret concoctions. By early 1951, an "almost revolutionary" method of producing rain was set to be inaugurated on the Medina Lake watershed. Will K. Stevens, "the flying rainmaker", said that little or no information was as yet available to the public regarding his method, since his process was still experimental and hadn't been patented. "We'll still use the silver iodide for upper strata clouds, but this new stuff is ideal for the low hanging clouds which have been filling the skies in this area for several days during the early morning hours (12)." By May of 1951, Medina Lake had barely risen, but some gave Stevens credit for a 12-inch rain that missed the lake. "He had been working the clouds like mad for nearly three hours but they didn't open up until they got past the Lake (13)." Also in 1951, the U.S. Congress considered allocating funds for intensive research in rainmaking (14). By 1959, the National Academy of Sciences had concluded that commercial rainmaking efforts had "no real scientific value" toward weather control (2). There was also the issue that if one did actually succeed in creating rain, you might get sued for it. In 1947 a rainmaking venture by Southwest Research Institute founder Tom Slick had apparently produced a good rain near Eagle Pass, and he settled out of court when sued by a cotton farmer whose field was flooded. Despite the legal liabilities and the scientific conclusions by the National Academy, in 1963 the South Texas Chamber of Commerce requested its Water Resources Committee to make a study on artificial rainmaking in south Texas (15). The committee heard from Dr. Harold V. Vagtborg, chairman of the board of Southwest Research Institute, who advised them "There are legal problems of authority, administration, and responsibility. There are problems of boundary. Man has not been able to control precisely the amount of rainfall he can induce, nor control the boundaries within which it may occur (16). In August, he had warned the Chamber "No matter how advanced, how severe the drought, there is always somebody who doesn't want it to rain." None of these issues stopped the U.S. military from developing cloud seeding as a weapon. In March of 1971 the public learned that since 1967, Air Force rainmakers had been operating secretly in the skies over the Ho Chi Minh trail network to hamper the logistics of the North Vietnamese. Washington columnist Jack Anderson noted the only trouble with rain is that "it falls on the just and the unjust alike. The same cloudbursts that have flooded the Ho Chi Minh trails reportedly have also washed out some Laotian villages. This is the reason, presumably, that the Air Force has kept its weathermaking triumphs in Indochina so secret (17)." With the secret about military rainmaking out in the open, there was no reason not to employ the technology back home. By June of 1971, specially equipped C-130 aircraft were criss-crossing the skies in drought-stricken south Texas. The first flight on June 6 was credited with expanding a rain-bearing cloud formation that dumped nearly an inch of rain over the Victoria area (18). Also in 1971, a rainmaking program was started by the Colorado River Municipal Water District. Their target area was about 3,600 square miles in the upper Colorado River basin upstream from Spence Reservoir. Their website reports:

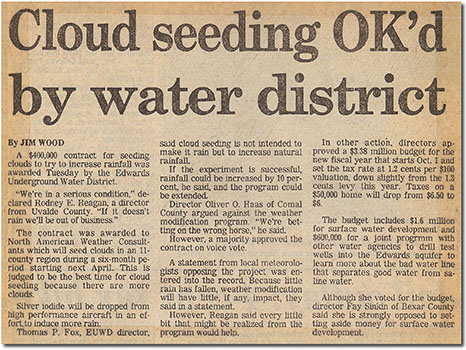

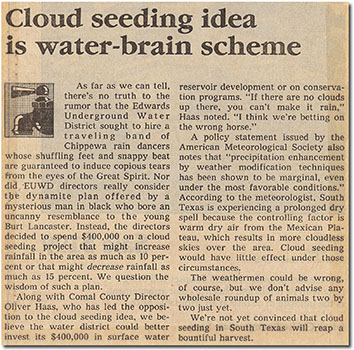

In 1984, in the midst of a lingering drought, the Edwards Underground Water District approved a $400,000 contract with North American Weather Consultants to initiate a cloud seeding effort in the Edwards region. The program drew immediate and vocal criticism. Local meteorologist Gary Grice, a National Weather Service forecaster, said the district would be wasting its money (20). In the end, the planes that would drop silver iodide never got off the ground and the program was shelved.

In 1986 the Southwest Cooperative Program was started as a cooperative effort between Oklahoma and Texas to randomly seed clouds over 5,000 square miles between Midland-Odessa and Lubbock. From 1986 to 1994, 93 seedings were performed and rainfall was compared with 90 non-seeded storm cells. The results indicated increased rainfall. Compared to the non-seeded cells, the seeded clouds increased in height by 7%, rainfall coverage increased by 43%, duration of storms increased 36%, and volume of rain increased 130% (21). In 1996, George Bomar, meteorologist for the Texas Natural Resources Conservation Commission, and State Senator Jeff Wentworth visited a number of South Texas government agencies and encouraged them to consider cloud seeding programs as a component of long term water management strategies (22). Bomar indicated state studies suggest cloud-seeding can increase the amount of rain by as much as 2.5 times. After the 1996 visits by Bomar and Wentworth (23), several agencies moved quickly to form the South Texas Weather Modification Association and initiate cloud seeding in May 1997 (24). The Evergreen Underground Water District and the counties of Wilson, Karnes, Frio, Atascosa, McMullen, Live Oak, and Bee agreed to share the cost of a three-year program. While there are disputes about whether or not cloud-seeding actually works, one thing for certain is it's not cheap. In San Angelo it cost $411,000 to seed above 7.2 million acres. The effort spearheaded by the Evergeeen District cost $282,000 per year. The first mission was flown along the Wilson-Atascosa county line on May 16, 1997, the same day the TNRCC granted the license to operate. Within hours, a large area received 1-4 inches of rainfall, but the National Weather Service said it would be very difficult to determine if the cloud-seeding caused it because a lot of heavy activity was expected anyway. In 1998 the Edwards Aquifer Authority set aside $500,000 for cloud-seeding and in July asked Governor George W. Bush to suspend the regulations requiring a state permit to conduct cloud seeding so they could begin a program immediately (25). The permit was tied up by protests of people living along creeks who feared that flooding would result; but it was eventually issued in October 1998 (26). The Authority gave assurances that no cloud-seeding would be conducted if severe storm warnings were issued, if storm clouds moved slowly and posed a flooding threat, or if storms continued to track over the same area. In January 1999 the Authority’s board approved a four year contract to conduct cloud seeding (27). The first scheduled effort on April 15, 1999 was canceled because there were no clouds (28). In June 2001, after several years of cloud-seeding efforts (29, 30), the Edwards Aquifer Authority board approved a study to determine if the amount of rain produced can be quantified (31). EAA General Manager Greg Ellis said "Here, we have a very unique situation with our rain gauges, our stream flow measures and our aquifer measures to actually determine as that rain is falling how much of that is benefitting the region, how much is actually getting to the ground and into the aquifer." In 2004, in light of the findings of the National Academy of Science (1), the EAA considered eliminating funding for cloud seeding, but eventually included $153,520 in their 2005 budget for cloud-seeding flights and an independent evaluation of previous efforts (32). In 2007, the EAA approved cloud seeding efforts for the ninth year in a row, and for the first time the program included a method to statistically evaluate the project's effectiveness. Four Board members voted against continuing the program, saying there was evidence that cloud seeding could actually decrease rainfall by accident, and they also had concerns about the EAA paying for scientific studies to investigate something the National Academy had already concluded doesn't work (33). In January of 2012, Dr. Roelof Bruintjes from the National Center for Atmospheric Research made a presentation to the EAA in hopes of building support for a research project to further investigate the effectiveness of cloud seeding. Dr. Bruintjes contended that new radar and satellite technologies and new airborne instruments could be used to quantify the effects of cloud seeding techniques. The EAA declined to fund the study, but continued to fund its own precipitation enhancement efforts with $151,000 in its 2013 Operating Budget. In late 2013 it proposed to spend $155,530 on the program in 2014. The latest version of the Texas State Water Plan issued in 2012 estimates that by 2060, weather modification could account for only 0.2% of the State's water needs (34).

|

||||||||

|

Materials used to prepare

this section: (1) "Cloud-seeding gets a failing grade", San Antonio Express-News, October 20, 2003. (2) "Commercial rainmaking efforts reported to provide no real scientific value", San Antonio Express, December 28, 1959. (3) "Proposed rainmaking: Dyrenforth's methods will probably be tried here soon", San Antonio Daily Express, April 17, 1892. (4) "Rainmaking experiments: progress for the arrangements of carrying on operations", San Antonio Daily-News, April 29, 1892. (5) "The rainmakers: an important meeting held and arrangements made to experiment", San Antonio Daily Light, November 14, 1892. (6) "The rainmakers welcomed", The Daily Light, November 15, 1892. (7) "Gone but not forgotten", The Daily Light, December 2, 1892. (8) "Echoes from West End", The Daily Light, December 3, 1892. (9) "A sensible suggestion", The San Antonio Daily Express, January 16, 1892. (10) "Rainmakers fail to offer relief", San Antonio Express, June 3, 1934. (11) "Drought and experiments in rainmaking", San Antonio Express, September 11, 1850. (12) "Rainmaking 'secret weapon' being tested", San Antonio Express, January 22, 1951. (13) "Big rain just misses Medina Lake", San Antonio Express, May 13, 1951. (14) "Washington report", San Antonio Light, August 2, 1951. (15) "Plan to close Consulate draws STCC protest", San Antonio Express, August 8, 1963. (16) "South Texas Chamber to study rainmaking", The Light, October 3, 1963. (17) "Rainmakers military success", San Antonio Express, March 18, 1971. (18) "Seeding flight due", The Light, June 7, 1971. (19) from CRMWD website at www.crmwd.org/crmwd_engineering_weathermod.htm, accessed January 5, 2014. (20) "Cloud seeding may be all wet" San Antonio Light, August 16, 1984. (21) Woodley, W.L. and D. Rosenfeld, 1993. Effects of cloud seeding in Texas. Journal of Applied Meteorology. 32:1844-1866. (22) "Council eyes cloud seeding" San Antonio Express-News, August 16, 1996. (23) "S.A. lawmaker urges cloud-seeding option"San Antonio Express-News, October 2, 1996. (24) "Storms follow cloud seeding" San Antonio Express-News, May 21, 1997. (25) "Board pushes cloud seeding" San Antonio Express-News, July 28, 1998. (26) "Aquifer authority wins cloud seeding permit from TNRCC" San Antonio Express-News, October 23, 1998. (27) "EAA to consider cloud-seeding deal"San Antonio Express-News, January 1, 1999. (28) "Cloud-seeding canceled on account of no clouds" San Antonio Express-News, April 16, 1999. (29) "Cloud seeding efforts take off in South Texas" San Antonio Express-News, May 4, 1999. (30) "Cloud seeding may get early start today"San Antonio Express-News, March 2, 2000. (31) "EAA OKs study of cloud seeding" San Antonio Express-News, June 19, 2001. (32) "Aquifer authority boosts fee" San Antonio Express-News, November 10, 2004. (33) "Cloud seeding concerns some panelists" San Antonio Express-News, April 11, 2007. (34) "Water for Texas: Summary of the 2011 Regional Water Plans." Prepared by the TWDB for the 82nd Legislative Session. |

||||||||