|

|

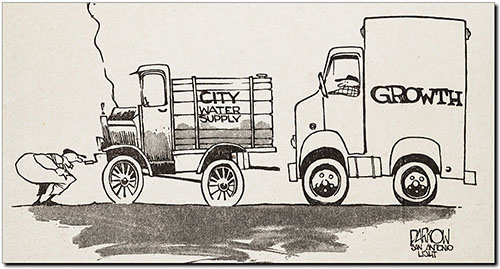

Alternatives to the Edwards Aquifer For many decades, citizens of San Antonio were very proud their entire municipal supply of water was pure, clean groundwater from the Edwards Aquifer. No other large city in the world could claim such a pure, abundant source. Today, San Antonio receives water from many other sources, and citizens have learned it is just as good as Edwards water. In fact, modern treatment methods can produce water that people might consider superior. Edwards water is very hard and is famous for producing a thick scale that quickly ruins water heaters and fixtures. More soap is required to clean things, and lots of people prefer the taste of softer water to Edwards water. Regardless of what people may like or dislike about Edwards water, the supply became limited by law in 1994. So if San Antonio and the surrounding region were to continue to grow, it became necessary for water users of the region to make big decisions and long-term commitments about developing new water resource alternatives. This section lists and discusses many of the various alternatives that have been studied and proposed by regional water purveyors and entities. Some have already been implemented, some abandoned for now, and others are in progress. There are also a few things that can be done to increase or better manage the Edwards supply, such as using recycled water, conservation, and building recharge dams. These will be discussed here as well. A Little Background.... In decades past, San Antonio was a world-leading pioneer in developing and managing water resources. The large scale use of recycled water for cooling electrical generating plants was first accomplished here (see section on Using Recycled Water), and San Antonio's desire to participate in the Canyon Lake project in the 1950's also illustrates that it had vision and leadership and a commitment to broadening and diversifying its water resources. However, back then, the Texas courts told San Antonio it didn't need water from elsewhere because it had not fully exploited the resources in its own river basin, including the Edwards Aquifer (see the Canyon Lake story). For decades, many projects and alternatives were debated and endlessly studied, but no progress was made. San Antonio got a reputation as a do-nothing city, where lack of confidence in the future water supply stood in the way of growth. In December 1996 State legislator Ron Lewis urged the State to take the lead in addressing San Antonio's future water needs, saying the city lacked the political will to do it on it's own (1). Again in 1997, senators on the State's Natural Resources Committee sharply criticized San Antonio for neglecting water issues. They said San Antonio lacked foresight and was not willing to "belly up to the bar" (2).

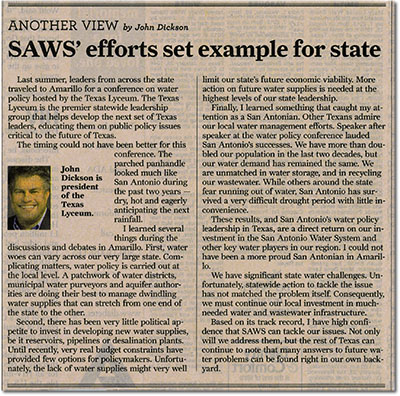

All this has changed and San Antonio has once again emerged as a world-leading pioneer in developing and managing water resources. In 1996 Mayor Bill Thornton formed a Citizens Committee on Water Policy and charged them with recommending a long term strategy for the San Antonio area. Their report urged that people recognize the complexity of the problem, and it outlined many possible solutions such as weather modification, aquifer optimization, and reusing water. From 1996 to 1998, the San Antonio Water System held 61 public meetings, worked closely with the public and all interested parties, built on the Citizen's Committee recommendations, and developed a 50-year water plan that was approved by City Council in November of that year. It contained a wide range of policies and options including a Canyon Lake pipeline, recycling water, increased water rates, conservation, aquifer storage and recovery systems, and eventual construction of new reservoirs. Since then, San Antonio has produced several iterations of a Water Management Plan and continues to remain at the forefront of water resource development.

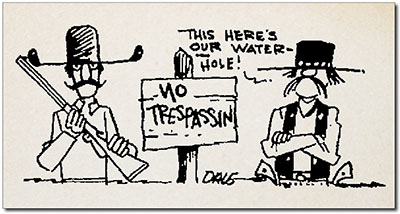

In December 2005, Region L planners appeared to be on track to complete a required five year review of the region's section of the State Water Plan, but it all fell apart in January '06. Amid squabbling and finger-pointing, the Region L Planning Group missed the January 4 deadline for including their work in the larger State plan. The group asked for an extension, but the State said the law did not provide for that and it assumed control of planning for the region. Most of the blame for the failure of the group to agree on an updated plan was directed at SAWS, which in 2005 dropped its participation in the Guadalupe River component of the plan. Other agencies complained that it was a huge problem for them to adjust and respond to SAWS decision. The flash-point, however, was a controversial Carrizo Aquifer component of the plan. The Planning Group voted 13-7 to remove it from the plan. Fourteen votes were required for removal, however, and the element stayed in. Two weeks after the deadline, the Group eventually approved a plan and also voted to include a letter stating that not everyone agreed to everything in the plan. The State said the Group's work would not be included in the official State plan but that it would consider their recommendations. It also said that failure to have an approved plan from Region L would affect the Region's ability to get loans and grants from the State and that special waivers would be required. In February of 2009, SAWS proposed a revised approach that would involve planning for SAWS' service area only. The new SAWS plan included a buying program for Edwards water rights and an expansion of the ASR project. It also includes recharge enhancement and evaluating recirculation, and a scaled-back brackish water desalination facility. A project to bring water from the Colorado River was left in the revised plan as a potential supply, although in January of 2009 the cost estimate for this project rose dramatically while water availability was cut to half the initial expectation. (9) SAWS' 2009 plan acknowledged the extremely difficult regulatory environment surrounding groundwater supply efforts in Texas. In the last several years, there has been an explosion of Groundwater Conservation Districts that have the power to regulate and limit transfers of water to San Antonio. In pursuing projects like a regional Carrizo Aquifer supply and a multi-county desalination wellfield, SAWS has met stiff opposition from local landowners and districts who simply do not want any water to be transferred to San Antonio. On the other side of the coin, SAWS has a very serious responsibility to provide adequate water for a growing city of over one million people, and failure in this task is not an option. In January of 2011, SAWS issued a formal request for proposals for new water supply projects that would provide an alternative water source and help diversify the city’s long-term water supplies. The objective was to identify projects that could provide 20,000 acre-feet per year to San Antonio by 2030, and 60,000 acre-feet by 2060. (10) Nine proposals were received, and in April of 2012 the list of projects under consideration was narrowed to four. SAWS anticipated that sometime in 2013 or early 2014, it would make an announcement regarding whether one or more of the proposals will be accepted. One proposal involved pumping from the Edwards-Trinity in Val Verde county west of San Antonio, and the other three involve pumping from the Carrizo and Queen City aquifers south and east of San Antonio. (11) SAWS' plan was updated again in 2012, sooner than initially expected, because of demographic, political, and environmental changes that made it prudent to revisit the alternatives being considered. The plan calls for investment in new supplies and a renewed commitment to conservation, and is considered a work in progress. In October of 2013, SAWS announced that it was making progress on selecting one of the four projects it has been reviewing. CEO Robert Puente said "We will recommend to our board, later on this year, maybe in January, as to who we want to negotiate with." (12) No sooner had it done so than significant opposition began to emerge to the project that involves pumping water from the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer in Val Verde county. Opponents packed a SAWS Board meeting in hopes of pressuring SAWS to reject the proposal. They cited impacts on creeks that support the threatened Devil's River minnow, and claimed that models by the Texas Water Development Board have overestimated the amount of groundwater available (13). Del Rio Mayor Roberto Fernandez said "I certainly appreciate SAWS looking out for its citizens and with the growth you're experiencing, I have no problem with that. Where we have a problem, in our part of the state, is that they not use our water." (14) A second proposal from Dimmit County prompted the local Wintergarden Groundwater Conservation District, from which permits would be needed, to pass a resolution to “specifically oppose the exportation of large quantities of groundwater from Dimmit and Val Verde counties, as is being considered by the San Antonio Water System.”

In February of 2014, SAWS announced it would recommend to its Board of Trustees that it accept none of the proposed projects and instead focus on an expansion of desalination closer to home in a partnership with CPS Energy to co-locate new water and power facilities (15). The highest-ranked proposal, that of Abengoa Water LLC to bring Carrizo Aquifer water from east of Austin, could not actually guarantee any water, but it did guarantee payments. SAWS CEO Robert Puente said “The highest ranked proposal was unwilling to assume the risk of water being cut off by the groundwater district that regulates the supply. We are unwilling to ask our ratepayers to absorb the cost of a project with potentially no water.” The request for new water supplies issued by SAWS was meant to shift all risk to a private developer, calling for the developer to build the project and deliver water to a local SAWS pump station. The business community responded to SAWS announcement by releasing a study that spelled out dire economic consequences if only a small shortfall of water were to occur (see study). SAWS countered by pointing out that water for business and industry would never be cut because it has the supplies to support economic growth. In a statement SAWS said "The only cuts we require of our customers is for lawn and landscape irrigation." (16) In any case, SAWS Board voted to continue discussions with Abengoa Water, but also defended the staff recommendation. Chairman Berto Guerra said "While I appreciate comments from various members of the public, I do not want to commit our ratepayers to $85 million per year for 30 years for a project that may or may not deliver on its promise. We stand together as a Board. We stand behind our Mayor. We stand behind Robert Puente." (17) Eventually, a deal was reached with Abengoa, which had brought in other partners and became known as the Vista Ridge Consortium. The new deal was far better for San Antonio than what was initially proposed. The city would pay only for water delivered, and there would be no price increases for 30 years. At the end of the term, San Antonio would own the 142-mile pipeline. The deal was approved by both SAWS Board and City Council (18) and construction began in 2016. The project is expected to be online in early 2020 and will provide up to 50,000 acre-feet per year. Some of the alternatives discussed below are no longer being pursued by San Antonio but could possibly be developed by other cities or entities. The Alternatives.... |

||||||||

|

Materials used to prepare this section: (1) "State urged to lead

S.A. to new water" San Antonio Express-News, December 13, 1996. |